Space Age

| |

Video of Neil Armstrong and the first step on the Moon. Apollo 11, being the first spaceflight mission that landed humans on the Moon, is one of the most significant moments in the Space Age. | |

The Space Age is a period encompassing the activities related to the space race, space exploration, space technology, and the cultural developments influenced by these events, beginning with the launch of Sputnik 1 on October 4, 1957,[1] and continuing to the present.

This period is characterized by changes in emphasis on particular areas of space exploration and applications. Initially, the United States and the Soviet Union invested unprecedented amounts of resources in breaking records and being first to meet milestones in crewed and uncrewed exploration. The United States established the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and the USSR established the Kosmicheskaya programma SSSR to meet these goals. This period of competition gave way to cooperation between those nations and emphasis on scientific research and commercial applications of space-based technology.[2][3]

Eventually other nations became spacefaring. They formed organizations such as the European Space Agency (ESA), the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO), and the China National Space Administration (CNSA). When the USSR dissolved the Russian Federation continued their program as Roscosmos.[2][3]

In the early 2020s, some journalists have used the phrase "New Space Age" in reference to a resurgence of innovation and public interest in space exploration as well as commercial applications of low Earth orbit (LEO) and more distant destinations. New developments include the participation of billionaires in crewed space travel, including space tourism and interplanetary travel.[4][5]

Periodization

[edit]The periodization of the Space Age can differ substantially, with some differentiating between a first Space Age and a second Space Age, which are separated at the turn of the 1980s/1990s.[6]

Periods

[edit]Foundational developments to suborbital spaceflights

[edit]

Some vehicles reached suborbital space much earlier than the launch of Sputnik. In June 1944, a German V-2 rocket became the first manmade object to enter space, albeit only briefly.[7] In March 1926 American rocket pioneer Robert H. Goddard launched the world's first liquid fuel rocket but it did not reach outer space.[8]

Since Germans undertook the sub-orbital V-2 rocket flight in secrecy, it was not initially public knowledge. Also, the German launches, as well as the subsequent sounding rocket tests performed in both the United States and the Soviet Union during the late 1940s and early 1950s, were not considered significant enough to define the start of the space age because they did not reach orbit. A rocket powerful enough to reach orbit could also be used as an intercontinental ballistic missile, that could deliver a warhead to any location on Earth. Some commentators claim this is why the orbital standard is commonly used to define when the space age began.[7]

1957 to 1970s/1980s: Establishment and Space Race

[edit]The Space Race was the first era of the Space Age. It was a race between the United States and the Soviet Union which began with the Soviet Union's October 4, 1957, launch of Earth's first artificial satellite Sputnik 1 during the International Geophysical Year.[9] Weighing 83.6 kg (184.3 lb) and orbiting the Earth once every 98 minutes.[9][10] The race resulted in rapid advances in rocketry, materials science, and other areas. One of the underlying motivations for the space race was military. The two nations were also in a nuclear arms race following the Second World War. Both nations made use of German missile technology and scientists from their missile program. The advantages, in aviation and rocketry, required for delivery systems were seen as necessary for national security and political superiority.[11]

The Cold War era competition between the United States and Soviet Union is one of the reasons the space age happened at that time. Since then the space age continues for the generation of scientific knowledge, the innovation and creation of markets, inspiration, and agreements between the space-faring nations.[12] Other reasons for the continuation of the space age are defending Earth from hazardous objects like asteroids and comets.[13]

Much of the technology developed for space applications has been spun off and found additional uses, such as memory foam. In 1958 the United States launched its first satellite, Explorer 1. The same year President Dwight D. Eisenhower created the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, commonly known as NASA.[14]

Prior to the first attempted human spaceflight, various animals were flown into outer space to identify potential detrimental effects of high g-forces in takeoff and landing, microgravity, and radiation exposure at high altitudes.[15]

The Space Race reached its peak with the Apollo program that captured the imagination of much of the world's population.[16] From 1961 to 1964, NASA's budget was increased almost 500 percent, and the lunar landing program eventually involved some 34,000 NASA employees and 375,000 employees of industrial and university contractors. The Soviet Union proceeded tentatively with its own lunar landing program which it did not publicly acknowledge, partly due to internal debate over its necessity and the untimely death (in January 1966) of Sergey Korolev, chief engineer of the Soviet space program.[14]

The landing of Apollo 11 was watched by over 500 million people around the world and is widely recognized as one of the defining moments of the 20th century. Since then, public attention has largely moved to other areas.[17]

The last major leap of in the USSR-USA Space Race was the Skylab and Salyut programs, which established the first space stations for the U.S. and USSR in Earth orbit following termination of both countries' moon programs.[18]

At the conclusion of the Apollo program, crewed flights from the United States were rare, then ended while the shuttle program was getting ready to kick into gear, and the space race had been over since the Apollo-Soyuz test project of 1975, started a period of U.S.–Soviet co-operation. The Soviet Union continued using the Soyuz spacecraft.[19]

The shuttle program restored spaceflight to the U.S. following the Skylab program, but the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster in 1986 marked a significant decline in crewed Shuttle launches. Following the disaster, NASA grounded all Shuttles for safety concerns until 1988.[20] During the 1990s funding for space-related programs fell sharply as the remaining structures of the now-dissolved Soviet Union disintegrated and NASA no longer had any direct competition,[21] engaging rather in more substantial cooperation like the Shuttle-Mir program and its follow-up the International Space Station.

Diversification

[edit]

While participation of private actors and other countries beside the Soviet Union and the United States in spaceflight had been the case from the very start of spaceflight development. A first commercial satellite had been launched by 1962, as well as in 1965 a third country achieving orbital spaceflight. The very beginning of the space age, the launch of Sputnik was in the context of international exchange, the International Geophysical Year 1957. Also soon into the space age the international community came together starting to negotiate dedicated international law governing outer space activity.

In the 1970s the Soviet Union started to invite other countries to fly their people into space through its Intercosmos program and the United States started to include women and people of colour in its astronaut program.

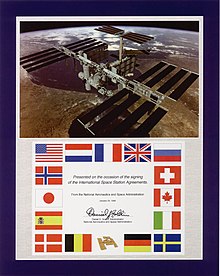

First exchange between the United States and the Soviet Union was formalized in the 1962 Dryden-Blagonravov agreement, calling for cooperation on the exchange of data from weather satellites, a study of the Earth's magnetic field, and joint tracking of the NASA Echo II balloon satellite.[22] In 1963 President Kennedy could even interest premier Khrushchev in a joint crewed Moon landing,[23][24] but after the assassination of Kennedy in November 1963 and Khrushchev's removal from office in October 1964, the competition between the two nations' crewed space programs heated up, and talk of cooperation became less common, due to tense relations and military implications. Only later the United States and the Soviet Union slowly started to exchange more information and engage in joint programs, particularly in the light of the development of safety standards since 1970,[25] producing the co-developed APAS-75 and later docking standards. Most notably this signaled the ending of the first era of the space age, the Space Race, through the Apollo-Soyuz mission which became the basis for the Shuttle-Mir program and eventually the International Space Station programme.

Such international cooperation, and international spaceflight organization was furthermore fueled by increasingly more countries achieving spaceflight capabilies and together with a by the 1980s established private spaceflight sector, both being embodied by the European Space Agency. This allowed the formation of an international and commercial post-Space Race spaceflight economy and period, with by the 1990s a public perception of space exploration and space-related technologies as being increasingly commonplace.[26]

This increasingly cooperative diversification persisted until competition started to rise in this diversified conditions, from the 2010s and particularly by the early 2020s.

2010s to present: New Space competition

[edit]

In the early 21st century, the Ansari X Prize competition was set up to help jump-start private spaceflight.[27] The winner, Space Ship One in 2004, became the first spaceship not funded by a government agency.[28]

Several countries now have space programs; from related technology ventures to full-fledged space programs with launch facilities.[29] There are many scientific and commercial satellites in use today, with thousands of satellites in orbit, and several countries have plans to send humans into space.[30][31] Some of the countries joining this new race are France, India, China, Israel and the United Kingdom, all of which have employed surveillance satellites. There are several other countries with less extensive space programs, including Brazil, Germany, Ukraine, and Spain.[32]

As for the United States space program, NASA permanently grounded all U.S. Space Shuttles in 2011. NASA has since relied on Russia and SpaceX to take American astronauts to and from the International Space Station.[26][33] NASA is currently constructing a deep-space crew capsule named the Orion. NASA's goal with this new space capsule is to carry humans to Mars. The Orion spacecraft is due to be completed in the early 2020s. NASA is hoping that this mission will "usher in a new era of space exploration."[32]

Another major factor affecting the current Space Age is the privatization of space flight.[34] A significant private spaceflight company is SpaceX which became the proprietor of one of world's most capable operational launch vehicle when they launched their current largest rocket, the Falcon Heavy in 2018. Elon Musk, the founder and CEO of SpaceX, has put forward the goal of establishing a colony of one million people on Mars by 2050 and the company is developing its Starship launch vehicle to facilitate this. Since the Demo-2 mission for NASA in 2020 in which SpaceX launched astronauts for the first time to the International Space Station, the company has maintained an orbital human spaceflight capability. Blue Origin, a private company founded by Amazon.com founder Jeff Bezos, is developing rockets for use in space tourism, commercial satellite launches, and eventual missions to the Moon and beyond.[35] Richard Branson's company Virgin Galactic is concentrating on launch vehicles for space tourism.[36] A spinoff company, Virgin Orbit, air-launches small satellites with their LauncherOne rocket. Another small-satellite launcher, Rocket Lab, has developed the Electron rocket and the Photon satellite bus for sending spacecraft further into the Solar System, the company also plans to introduce the larger Neutron launch vehicle in 2025.[37]

Elon Musk has the stated that the main reason he founded SpaceX is to make humanity a multiplanetary species, and cites reasons for doing it including: To ensure the long-term continuation of our species and protecting the "light of consciousness".[38][39] He also said,

You want to wake up in the morning and think the future is going to be great - and that's what being a spacefaring civilization is all about. It's about believing in the future and thinking that the future will be better than the past. And I can't think of anything more exciting than going out there and being among the stars.[40]

The Space Age marked a major comeback and return with the launch of NASA's Space Launch system during the Artemis I mission on November 16, 2022; it marked the first time a human rated spacecraft had been to the Moon in nearly 50 years, as well as the return of United States capability to get astronauts to the Moon with the Space Launch System and Orion.[41] Additional goals for the 2020s include completion of the Lunar Gateway, mankind's first space station around the Moon, and the first crewed moon landing since the Apollo era with Artemis III.

The U.S. Military has also joined the new space age with the creation of the new Space Force on December 20th 2019.

Chronology

[edit]| History of technology |

|---|

| Date | First | Project | Participant | Country |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| June 20, 1944 | Artificial object in outer space, i.e. beyond the Kármán line | V-2 rocket MW 18014 test flight[42] | – N/A | Germany |

| October 24, 1946 | Pictures from space (105 km)[43][44][45] | U.S.-launched V-2 rocket from White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico. | – N/A | United States |

| February 20, 1947 | Animals in space | U.S.-launched V-2 rocket on 20 February 1947 from White Sands Missile Range, New Mexico.[46][47][48] | - fruit flies | United States |

| October 4, 1957 | Artificial satellite | Sputnik 1[49] | – N/A | Soviet Union |

| November 3, 1957[50] | Animal in orbit | Sputnik 2[51] | Laika the dog | Soviet Union |

| January 2, 1959 | Lunar flyby, spacecraft to achieve a heliocentric orbit | Luna 1[52] | – N/A | Soviet Union |

| September 12, 1959 | Impact on the Lunar surface; thereby becoming the first human object to reach another celestial body | Luna 2[53] | – N/A | Soviet Union |

| October 7, 1959 | Pictures of the far side of the Moon, first spacecraft to use Gravity assist | Luna 3[54][55] | – N/A | Soviet Union |

| January 31, 1961 | Hominidae in space | Mercury-Redstone 2[56] | Ham (chimpanzee) | United States |

| April 12, 1961 | Human in space | Vostok 1[57][58] | Yuri Gagarin | Soviet Union |

| May 5, 1961 | Manual orientation of crewed spacecraft. | Freedom 7 (Mercury-Redstone 3)[59] | Alan Shepard | United States |

| December 14, 1962 | Successful flyby of another planet (Venus closest approach 34,773 kilometers) | Mariner 2[60] | – N/A | United States |

| March 18, 1965 | Spacewalk | Voskhod 2[61][62] | Alexei Leonov | Soviet Union |

| December 15, 1965 | Space rendezvous | Gemini 6A[63] and Gemini 7[63] | Schirra, Stafford, Borman, Lovell | United States |

| February 3, 1966 | Soft landing on the Moon by a spacecraft | Luna 9[64][65] | – N/A | Soviet Union |

| March 1, 1966 | Human-made object to impact another planet | Venera 3[66][67] | – N/A | Soviet Union |

| March 16, 1966 | Orbital docking between two spacecraft | Gemini 8[68] & Agena Target Vehicle[69] | Neil Armstrong, David Scott | United States |

| April 3, 1966 | Artificial satellite of another celestial body (other than the Sun) | Luna 10[70] | – N/A | Soviet Union |

| October 18, 1967 | Telemetry from the atmosphere of another planet | Venera 4[71] | – N/A | Soviet Union |

| December 21–27, 1968 | Humans to orbit the Moon | Apollo 8 | Borman, Lovell, Anders | United States |

| July 20, 1969 | Humans land and walk on the Moon | Apollo 11[72] | Neil Armstrong, Buzz Aldrin | United States |

| December 15, 1970 | Telemetry from the surface of another planet | Venera 7[73] | – N/A | Soviet Union |

| April 19, 1971 | Operational space station | Salyut 1[74][75] | – N/A | Soviet Union |

| June 7, 1971 | Resident crew | Soyuz 11 (Salyut 1) | Georgy Dobrovolsky, Vladislav Volkov, Viktor Patsayev | Soviet Union |

| July 20, 1976 | Pictures from the surface of Mars | Viking 1[76] | – N/A | United States |

| April 12, 1981 | Reusable orbital spaceship | STS-1[77] | Young, Crippen | United States |

| February 19, 1986 | Long-duration space station | Mir[78] | – N/A | Soviet Union |

| February 14, 1990 | Photograph of the whole Solar System[79] | Voyager 1[80] | – N/A | United States |

| November 20, 1998 | Current space station | International Space Station[81] | – N/A | Russia |

| August 25, 2012 | Interstellar space probe | Voyager 1[82] | – N/A | United States |

| November 12, 2014 | Artificial probe to soft-land on a comet (67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko)[83] | Rosetta[84] | – N/A | European Space Agency |

| July 14, 2015 | Space probes to explore all major planets recognized in 1981[85] | New Horizons[86] | – N/A | United States |

| December 20, 2015 | Vertical landing of an orbital rocket booster on a ground pad.[87] | Falcon 9 flight 20[88] | – N/A | United States |

| April 8, 2016 | Vertical landing of an orbital rocket booster on a floating platform at sea.[89] | SpaceX CRS-8[90] | – N/A | United States |

| March 30, 2017 | Relaunch and second landing of a used orbital rocket booster.[91] | SES-10[92] | – N/A | United States |

| January 3, 2019 | Soft landing on the lunar far side | Chang'e 4[93][94] | – N/A | China |

| May 30, 2020 | Human orbital spaceflight launched by a private company | Crew Dragon Demo-2/Crew Demo-2/SpaceX Demo-2/Dragon Crew Demo-2[95] | Bob Behnken, Doug Hurley | United States |

| April 19, 2021 | First powered controlled extraterrestrial flight by an aircraft | Ingenuity as part of NASA's Mars 2020 mission | – N/A | United States |

| July 11, 2021 | Commercial space tourism flight | Virgin Galactic Unity 22[96] | David Mackay, Michael Masucci, Sirisha Bandla, Colin Bennet, Beth Moses, Richard Branson | United States |

| October 5, 2021 | Feature-length fiction film shot in space (The Challenge) | Soyuz MS-19[97] | Anton Shkaplerov, Klim Shipenko, Yulia Peresild | Russia |

| November 16, 2022 | Artemis I launch restoring American capability to get humans to the Moon | Artemis I[98] | - N/A | United States |

Cultural influences

[edit]Arts and architecture

[edit]-

Iconic rocket ship-shaped tail lights and fins on a 1959 Cadillac Coupe de Ville

-

Satellite-influenced signage at the Town Motel in Birmingham, Alabama

-

TWA Moonliner II replica atop the restored TWA Corporate Headquarters building in Kansas City, MO, 2007

-

The Space Needle, in Seattle WA, resembles a UFO and draws inspiration from the Space Age.

The Space Age is considered to have influenced:

- Automotive design: Virgil Exner's Forward Look, 1957-1961

- Googie architecture

- Space Age fashions by André Courrèges, Pierre Cardin, Paco Rabanne, Rudi Gernreich,[99] Emanuel Ungaro, Jean-Marie Armand,[100] Michèle Rosier, and Diana Dew

- Furniture design of the 1950s and '60s by Eero Saarinen, Arne Jacobsen, Eero Aarnio, and Verner Panton

- Amusement park attractions, such as TWA Moonliner and Mission: Space.

- Cold War playground equipment

Music

[edit]The Space Age also inspired musical genres:[citation needed]

See also

[edit]- SEDS

- Information Age

- Jet Age

- Atomic Age

Spaceflight portal

Spaceflight portal Space portal

Space portal Solar system portal

Solar system portal World portal

World portal

References

[edit]- ^ Garcia, Mark (October 5, 2017). "60 years ago, the Space Age began". nasa.gov. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

On October 4, 1957, the Soviet Union opened the Space Age...

- ^ a b Williams, Matt (June 27, 2015). "What Is The Space Age?". universetoday.com. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ a b Federation, International Astronautical. "IAF : ROSCOSMOS". www.iafastro.org. Archived from the original on 9 February 2022. Retrieved 2022-02-09.

- ^ Pethokoukis, James (May 11, 2022). "America Is Launching a New Space Age. And It's a Problem That Many Americans Don't Know About It". aei.org. American Enterprise Institute. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ "To infinity and beyond: the new space age". euronews.com. euronews.next. February 2, 2022. Retrieved March 17, 2023.

- ^ Harrison, Todd; Cooper, Zack; Johnson, Kaitlyn; Roberts, Thomas G (2017). "Escalation & Deterrence in the Second Space Age". Unpublished. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.15240.11525. Retrieved 14 October 2024.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Schefter, James (1999), The Race: The Uncensored Story of How America Beat Russia to the Moon, New York, New York: Doubleday, pp. 3–49, ISBN 0-385-49253-7

- ^ "Goddard launches space age with historic first 85 years ago today". 16 March 2011. Retrieved 2016-04-29.

- ^ a b Garber, Steve. "Sputnik and The Dawn of the Space Age". History. NASA. Archived from the original on 18 November 2004. Retrieved 6 May 2013.

- ^ Chertok, Boris. "Rockets and People: Creating a Rocket Industry, p. 385" (PDF). History. NASA. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "Space Race Timeline". rmg.co.uk. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ^ "Space Race Timeline". calendar-canada.ca. calendar-canada. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ^ "Defend Earth". planetary.org. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ^ a b "The Space Race". HISTORY. 2010-02-22. Retrieved 2022-10-16.

- ^ "Animals in Space". NASA.

In the earlier days of space exploration, nobody knew if people could survive a trip away from Earth, so using animals was the best way to find out. In 1948, a rhesus macaque monkey named Albert flew inside a V2 rocket. In 1957, Russians sent a dog named Laika into orbit. Both of these flights showed that humans could survive weightlessness and the effects of high gravitational forces.

- ^ McDougall, Walter A (Winter 2010), "Shooting the Moon", American Heritage.

- ^ "National Aeronautics and Space Administration". NASA. Archived from the original on 1996-12-31. Retrieved 2015-11-20.

- ^ "The First Space Stations". Smithsonian Institution. 15 August 2023. Archived from the original on 2023-09-29. Retrieved 2023-08-15.

- ^ Lewis, Cathleen (2016-12-16). "Fifty Years of the Russian Soyuz Spacecraft". Smithsonian Institution.

- ^ Howell, Elizabeth. "Challenger: Shuttle Disaster That Changed NASA". Space.com. Archived from the original on 4 May 2018. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ^ Chatzky, Andrew (2021-09-23). "Space Exploration and U.S. Competitiveness". The Council on Foreign Relations.

- ^ "The First Dryden-Blagonravov Agreement – 1962". NASA History Series. NASA. Archived from the original on 1 August 2020. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Launius, Roger D. (2019-07-10). "First Moon landing was nearly a US–Soviet mission". Nature. 571 (7764): 167–168. Bibcode:2019Natur.571..167L. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-02088-4. PMID 31292553. S2CID 195873630.

- ^ Sietzen, Frank (October 2, 1997). "Soviets Planned to Accept JFK's Joint Lunar Mission Offer". SpaceDaily. SpaceCast News Service. Retrieved August 1, 2013.

- ^ Helen T. Wells; Susan H. Whiteley; Carrie E. Karegeannes (1975). "Origins of NASA Names: Manned SpaceFlight". NASA. Retrieved 2 November 2015.

- ^ a b NASA. Historical Studies in the Societal Impact of Spaceflight - NASA (PDF).

- ^ "Ansari X Prize". Archived from the original on 23 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-15.

- ^ "SpaceShipOne: The First Private Spacecraft | The Most Amazing Flying Machines Ever". Space.com. Archived from the original on 2015-11-15. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ "Global Space Programs | Space Foundation". www.spacefoundation.org. Archived from the original on 2015-11-14. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ "Japan Wants Space Plane or Capsule by 2022". Space.com. 24 October 2012. Archived from the original on 2015-12-24. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ "India takes giant step to manned space mission". Telegraph.co.uk. 19 December 2014. Archived from the original on 2015-11-26. Retrieved 2015-11-27.

- ^ a b "The New Space Race – Who Will Take the Lead?". rcg.org. Retrieved 2018-05-08.

- ^ "The New American Space Age: A Progress Report on Human SpaceFlight" (PDF). Aerospace Industries Association. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 March 2018. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ^ "Circumlunar mission". Space Adventures. 3 April 2014. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- ^ "Blue Origin: everything you need to know about the Amazon.com of space". TechRadar. Retrieved 2019-11-11.

- ^ "Sir Richard Branson plans orbital spaceships for Virgin Galactic, 2014 trips to space". foxnews.com.

- ^ "Rocket Lab Completes Archimedes Engine Build, Begins Engine Test Campaign". www.businesswire.com. 2024-05-06. Retrieved 2024-05-08.

- ^ Arevalo, Evelyn (April 24, 2021). "Elon Musk Founded SpaceX To Make Humans A Multi-Planet Species, 'Build A City On Mars'". tesmanian.com. TESMANIAN. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ^ Bates, Jordan (May 8, 2017). "In Order to Ensure Our Survival, We Must Become a Multi-Planetary Species". futurism.com. Camden Media Inc. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ^ Musk, Elon. "Mission". spacex.com. SpaceX. Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ^ "Liftoff! NASA's Artemis I Mega Rocket Launches Orion to Moon?". nasa.gov. 16 November 2022. Retrieved 2022-11-26.

- ^ "Long-range" in the context of the time. See NASA history article Archived 7 January 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Chronology: Cowboys to V-2s to the Space Shuttle to lasers". www.wsmr.army.mil. Archived from the original on 13 October 2014. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ "First Pictures from Space". Archived from the original on 2014-02-21. Retrieved 2013-01-17.

- ^ Reichhardt, Tony. "First Photo From Space". airspacemag.com. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ "Post War Space". postwar.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-15.

- ^ "The Beginnings of Research in Space Biology at the Air Force Missile Development Center, 1946–1952". History of Research in Space Biology and Biodynamics. NASA. Archived from the original on 25 January 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- ^ "V-2 Firing Tables". White Sands Missile Range. Archived from the original on 25 January 2008. Retrieved 31 January 2008.

- ^ Terry, Paul (2013), Top 10 Of Everything, Octopus Publishing Group Ltd 2013, p. 233, ISBN 978-0-600-62887-3

- ^ McDowell, Jonathan. "Satellite Catalog". Jonathan's Space Page. Retrieved 29 October 2013.

- ^ Berger, Eric (3 November 2017). "The first creature in space was a dog. She died miserably 60 years ago". Ars Technica. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2017.

- ^ "NSSDCA Luna-1". Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- ^ Harvey, Brian (2007). Soviet and Russian Lunar Exploration. Springer. Bibcode:2007srle.book.....H. ISBN 978-0-387-73976-2.

- ^ Harvey, Brian (2011). Russian space probes: scientific discoveries and future missions. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4419-8150-9.

- ^ Berger, Eric (4 October 2019). "All hail Luna 3, rightful king of 1950s space missions". Ars Technica. Retrieved 13 October 2023.

- ^ "My steps for Bataan". United States Marine Corps Flagship. Retrieved 13 April 2022.

- ^ Colin Burgess, Rex Hall (June 2, 2010). The first Soviet cosmonaut team: their lives, legacy, and historical impact. Praxis. p. 356. ISBN 978-0-387-84823-5.

- ^ "Yuri Gagarin: Who was the first person in space?". BBC. Retrieved 13 July 2022.

- ^ Swenson Jr., Loyd S.; Grimwood, James M.; Alexander, Charles C. (1989). "11-1 Suborbital Flights into Space". In Woods, David; Gamble, Chris (eds.). This New Ocean: A History of Project Mercury (url). NASA. Retrieved August 15, 2017.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "Mariner 2". U.S. National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved September 8, 2013.

- ^ Burgess, Colin; Hall, Rex (2009). The first Soviet cosmonaut team their lives, legacy, and historical impact (Online-Ausg. ed.). Berlin: Springer. p. 252. ISBN 978-0387848242.

- ^ Grayzeck, Dr. Edwin J. "Voskhod 2". nssdc.gsfc.nasa.gov. National Space Science Data Center. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ^ a b Hacker, Barton C.; Grimwood, James M. (September 1974). "Chapter 11 Pillars of Confidence". On the Shoulders of Titans: A History of Project Gemini. NASA History Series. Vol. SP-4203. NASA. p. 239. With Gemini IV, NASA changed to Roman numerals for Gemini mission designations.

- ^ "Chandrayaan-2 landing: 40% lunar missions in last 60 years failed, finds Nasa report". India Today. 7 September 2019.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (2018). Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration, 1958–2016 (PDF). The NASA history series (second ed.). Washington, D.C.: NASA History Program Office. pp. 1–2. ISBN 9781626830424. LCCN 2017059404. SP2018-4041.

- ^ Wade, Mark. "Venera 3MV-3". Encyclopedia Astronautica. Archived from the original on December 28, 2016. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ Krebs, Gunter. "Venera 3 (3MV-3 #1)". Gunter's Space Page. Retrieved 3 April 2018.

- ^ NASA (March 11, 1966). "Gemini 8 press kit" (PDF) (Press release). NASA. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2012. Retrieved February 27, 2015.

- ^ Agle, D. C. (September 1998). "Flying the Gusmobile". Air & Space.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (2018). Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration, 1958–2016 (PDF). The NASA history series (second ed.). Washington, D.C.: NASA History Program Office. p. 1. ISBN 9781626830424. LCCN 2017059404. SP2018-4041.

- ^ Siddiqi, Asif A. (2018). Beyond Earth: A Chronicle of Deep Space Exploration, 1958–2016 (PDF). The NASA history series (second ed.). Washington, D.C.: NASA. ISBN 9781626830424. LCCN 2017059404. SP2018-4041.

- ^ Orloff, Richard W. (2000). Apollo by the Numbers: A Statistical Reference. NASA History Series. Washington, D.C.: NASA History Division, Office of Policy and Plans. ISBN 978-0-16-050631-4. LCCN 00061677. OCLC 829406439. SP-2000-4029. Retrieved June 12, 2013.

- ^ "Science: Onward from Venus". Time. 8 February 1971. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008. Retrieved 2 January 2013.

- ^ Baker, Philip (2007). The Story of Manned Space Stations: An Introduction. Springer-Praxis Books in Astronomy and Space Sciences. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-30775-6.

- ^ Ivanovich, Grujica S. (2008). Salyut - The First Space Station: Triumph and Tragedy. Springer-Praxis Books in Astronomy and Space Sciences. Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-0-387-73585-6.

- ^ "Viking 1 approaches Mars". The Planetary Society.

- ^ "STS-1 Press Kit" (PDF). NASA. 1981. p. 36. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 28 November 2012.

- ^ Jackman, Frank (29 October 2010). "ISS Passing Old Russian Mir In Crewed Time". Aviation Week.

- ^ See "Voyagers". Archived from the original on 2009-03-31. Retrieved 2009-07-21. under "Extended Mission"

- ^ "Voyager - Mission Status". voyager.jpl.nasa.gov.

- ^ Gary Kitmacher (2006). Reference Guide to the International Space Station. Canada: Apogee Books. pp. 71–80. ISBN 978-1-894959-34-6. ISSN 1496-6921.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - ^ "Voyager - Mission Status".

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (Nov 12, 2014). "European Space Agency's Spacecraft Lands on Comet's Surface". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2014-11-12. Retrieved Nov 12, 2014.

- ^ Agle, D. C.; Brown, Dwayne; Bauer, Markus (30 June 2014). "Rosetta's Comet Target 'Releases' Plentiful Water". NASA. Retrieved 30 June 2014.

- ^ Talbert, Tricia (25 March 2015). "New Horizons: The First Mission to the Pluto System and the Kuiper Belt". nasa.gov. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 4 May 2018.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (July 18, 2015). "The Long, Strange Trip to Pluto, and How NASA Nearly Missed It". The New York Times. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- ^ Chang, Kenneth (December 21, 2015). "SpaceX Successfully Lands Rocket after Launch of Satellites into Orbit". The New York Times. Retrieved December 22, 2015.

- ^ "2015 U.S. Space Launch Manifest". americaspace.com. AmericaSpace, LLC. 21 December 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2015.

- ^ Drake, Nadia (April 8, 2016). "SpaceX Rocket Makes Spectacular Landing on Drone Ship". National Geographic. Archived from the original on April 8, 2016. Retrieved April 8, 2016.

To space and back, in less than nine minutes? Hello, future.

- ^ Hartman, Daniel W. (July 2014). "Status of the ISS USOS" (PDF). NASA Advisory Council HEOMD Committee. Retrieved October 26, 2014.

- ^ Grush, Loren (March 30, 2017). "SpaceX makes aerospace history with successful landing of a used rocket". The Verge. Archived from the original on March 30, 2017. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ "Space Systems Mission and system requirements for Electric Propulsion" (PDF). Airbus Defence and Space. 25 November 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 August 2016. Retrieved 31 August 2016.

- ^ Lyons, Kate. "Chang'e 4 landing: China probe makes historic touchdown on far side of the moon". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "China successfully lands Chang'e-4 on far side of Moon". Archived from the original on 3 January 2019. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- ^ "Crew Dragon SpX-DM2". Spacefacts. Retrieved 31 May 2020.

- ^ July 2021, Chelsea Gohd 11 (2021-07-11). "Virgin Galactic launches Richard Branson to space in 1st fully crewed flight of VSS Unity". Space.com. Retrieved 2021-08-10.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Clark, Anastasia (October 5, 2021). "Russian crew blast off to film first movie in space". Phys.org. Retrieved October 5, 2021.

- ^ "Liftoff! NASA's Artemis I Mega Rocket Launches Orion to Moon". Phys.org. November 16, 2022. Retrieved November 26, 2022.

- ^ "Fashion for the '70s: Rudi Gernreich Makes Some Modest Proposals". Life. Vol. 68, no. 1. 1970-01-09. pp. 115–118. Retrieved 2022-01-03.

- ^ "Jean-Marie Armand". Couture Allure Vintage Fashion. 2011-03-08. Retrieved 2021-12-13.

His designs were very modern and architectural, much like those of Courreges and Cardin.

External links

[edit]- Space Chronology, archived from the original on 2017-05-25, retrieved 2013-05-12

Interactive media

[edit]- 50th Anniversary of the Space Age & Sputnik, NASA, archived from the original on 2007-10-27.