L5 Society

The L5 Society was founded in 1975 by Carolyn Meinel and Keith Henson to promote the space colony ideas of Gerard K. O'Neill.[1]

In 1987, the L5 Society merged with the National Space Institute to form the National Space Society.[2]

Name[edit]

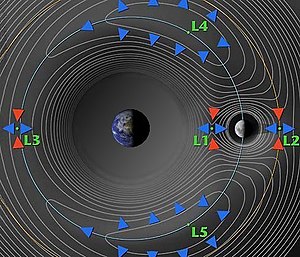

The name comes from the L4 and L5 Lagrangian points in the Earth–Moon system proposed as locations for the huge rotating space habitats that O'Neill envisioned. L4 and L5 are points of stable gravitational equilibrium located along the path of the Moon's orbit, 60 degrees ahead or behind it.[2]

An object placed in orbit around L5 (or L4) will remain there indefinitely without having to expend fuel to keep its position, whereas an object placed at L1, L2 or L3 (all points of unstable equilibrium) may have to expend fuel if it drifts off the point.

History[edit]

Founding of L5 Society[edit]

O'Neill's first published paper on the subject, "The Colonization of Space", appeared in the magazine Physics Today in September 1974. A number of people who later became leaders of the L5 Society got their first exposure to the idea from this article. Among these were a couple from Tucson, Arizona, Carolyn Meinel and Keith Henson. The Hensons corresponded with O'Neill and were invited to present a paper on "Closed Ecosystems of High Agricultural Yield" at the 1975 Princeton Conference on Space Manufacturing Facilities, which was organized by O'Neill.[3]

At this conference, O'Neill merged the Solar Power Satellite (SPS) ideas of Peter Glaser with his space habitat concepts.[4]

The Hensons incorporated the L5 Society in August 1975, and sent its first 4-page newsletter in September to a sign up list from the conference and O'Neill's mailing list.[2] The first newsletter included a letter of support from Morris Udall (then a contender for US president) and said "our clearly stated long range goal will be to disband the Society in a mass meeting at L5."[5]

Moon Treaty[edit]

The peak of L5's influence was the defeat of the Moon Treaty in the U.S. Senate in 1980 ("... L-5 took on the biggest political fight of its short life, and won").[3] Specifically, L5 Society activists campaigned for awareness of the provisions against any form of sovereignty or private property in outer space that would make space colonization impossible and the provisions against any alteration of the environment of any celestial body prohibiting terraforming. Leigh Ratiner [a Washington lawyer/lobbyist] "played the key role in the lobbying effort, although he had energetic help from L-5 activists, notably Eric Drexler and Christine Peterson."[3][6]

Although economic analysis[7] indicated the SPS/space colony concept had merit, it foundered on short political and economic horizons and the fact that the transport cost to space was about 300 times too high for individuals to fund when compared to the Plymouth Rock and Mormon colonies.[8]

Merger with National Space Institute[edit]

In 1986, the L5 Society, which had grown to about 10,000 members, merged with the 25,000 member National Space Institute, to form the present-day National Space Society. The National Space Institute had been founded in 1972 by Wernher von Braun, the former German rocket engineer of the WW II Nazi V-2 rocket/ballistic missile program, and of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center and Project Apollo program manager.[9]

While the L5 Society failed to achieve the goal of human settlements in space, it served as a focal point for many of the people who later became known in fields such as nanotechnology, memetics, extropianism, cryonics, transhumanism, artificial intelligence, and tether propulsion, such as K. Eric Drexler, Robert Forward, and Hans Moravec.[10][11]

L5 News[edit]

The L5 News was the newsletter of the L5 Society reporting on space habitat development and related space issues. The L5 News was published from September 1975 until April 1987, when the merger with the National Space Institute was completed and the newly formed National Space Society began publication of its own magazine, Ad Astra.

See also[edit]

- List of objects at Lagrangian points

- Home on Lagrange (The L5 Song)

- Planetary chauvinism

- Space advocacy organizations

- Space colonization topics

References[edit]

- ^ Dorminey, Bruce (July 31, 2012). "Death Of A Sci-Fi Dream: Free-Floating Space Colonies Hit Economic Reality". Forbes. Archived from the original on August 7, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ a b c Brandt-Erichsen, David (November 1994). "Brief History of the L5 Society". Ad Astra. No. Nov.-Dec., 1994. National Space Society. Retrieved December 17, 2018.

- ^ a b c Michaud, Michael A. G. (1986). "Chapter 5: O'Neills Children". Reaching for the High Frontier: The American Pro-Space Movement, 1972–84. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0275921514. Archived from the original on December 10, 2016.

- ^ O'Neill, Gerard K. (May 7–9, 1975). "The Space Manufacturing Facility Concept". Space Manufacturing Facilities: Space Colonies. Second Princeton/AIAA/NASA Conference on Space Manufacturing. Princeton, NJ: American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics. doi:10.2514/6.1975-2002.

- ^ "A Newsletter from the L-5 Society" (PDF). L-5 News. No. I. L-5 Society. September 1975. Retrieved December 21, 2022 – via National Space Society.

- ^ Henson, Carolyn (March 1980). "Moon Treaty Update". L5 News. L5 Society. Retrieved December 21, 2022 – via National Space Society.

- ^ O'Neill, Gerard K. (December 5, 1975). "Space Colonies and Energy Supply to the Earth: Manufacturing facilities in high orbit could be used to build satellite solar power stations from lunar materials". Science. 190 (4218): 943–947. doi:10.1126/science.190.4218.943.

- ^ Dyson, Freeman (January 1, 1979). "Pilgrims, Saints and Spacemen". Disturbing the Universe (1st ed.). New York: Harper & Row, Publishers. pp. 118–126. ISBN 9780060111083.

- ^ "NSS Mission & History". space.nss.org. National Space Society. Retrieved December 21, 2022.

- ^ Regis, Ed (1990). Great Mambo Chicken and the Transhuman Condition: Science Slightly over the Edge (PDF). Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-09258-1.

- ^ McCray, W. Patrick (December 9, 2012). The Visioneers: How a Group of Elite Scientists Pursued Space Colonies, Nanotechnologies, and a Limitless Future. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400844685.

External links[edit]

- NSS.org: Official NSS−National Space Society website

- NSS.org: Ad Astra Online — online edition of Ad Astra magazine.

- NSS Worldwide website

- Chapters.nss.org: National Space Society Chapters Network Resources for NSS chapters, members and space activists.

- NSS Chapters Story

- 1979 UN Declaration on the Moon (Moon Treaty)

- L5 News index

- Space organizations

- Space advocacy organizations

- Space colonization

- International scientific organizations

- Scientific societies based in the United States

- Scientific organizations established in 1975

- Organizations established in 1975

- Organizations disestablished in 1987

- 1975 establishments in the United States

- 1987 disestablishments in the United States