Owsley Stanley

This article needs additional citations for verification. (February 2019) |

Owsley Stanley | |

|---|---|

Stanley in 1967 at his arraignment | |

| Born | Augustus Owsley Stanley III January 19, 1935 Kentucky, U.S. |

| Died | March 12, 2011 (aged 76) Queensland, Australia |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names | Bear |

| Citizenship | Naturalised Australian |

| Occupation | Audio engineer |

| Known for | LSD, Wall of Sound |

| Title | "Patron of Thought" |

| Spouse | Sheilah Stanley |

| Children | 4 |

| Relatives | Augustus O. Stanley, grandfather |

| Website | www |

| Part of a series on |

| Psychedelia |

|---|

|

Augustus Owsley Stanley III (January 19, 1935 – March 12, 2011) was an American-Australian audio engineer and clandestine chemist. He was a key figure in the San Francisco Bay Area hippie movement during the 1960s and played a pivotal role in the decade's counterculture.[1]

Under the professional name Bear, he was the sound engineer for the Grateful Dead, recording many of the band's live performances. Stanley also developed the Grateful Dead's Wall of Sound, one of the largest mobile sound reinforcement systems ever constructed. Stanley also helped Robert Thomas design the band's trademark skull logo.[2]

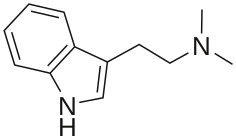

Called the Acid King by the media,[3][4] Stanley was the first known private individual to manufacture mass quantities of LSD.[5][6][7] By his own account, between 1965 and 1967, Stanley produced at least 500 grams of LSD, amounting to a little more than five million doses.[8]

He died in a car accident in Australia (where he had taken citizenship in 1996) on March 12, 2011.[7][9][10]

Ancestry

[edit]Stanley was the scion of a political family from Kentucky. His father was a government attorney. His paternal grandfather, Augustus Owsley Stanley, a member of the United States Senate after serving as Governor of Kentucky and in the U.S. House of Representatives, campaigned against Prohibition in the 1920s.[7]

Biography

[edit]Early life

[edit]When he was fifteen, Owsley spent fifteen months as a voluntary psychiatric patient in St. Elizabeths Hospital in Washington, D.C.[11] Without having graduated from high school, he was admitted to the University of Virginia, where he studied engineering for a year. Despite maintaining a 3.4 grade point average with minimal effort, he dropped out because of his disinclination for slide rules and mechanical drawing.[12][13] Despite his dearth of formal education, he secured a position as a test engineer with Rocketdyne in Los Angeles; in this capacity, he worked on the SM-64 Navaho supersonic cruise missile. In June 1956, he enlisted in the United States Air Force as an electronics specialist, serving for 18 months (including stints at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and Edwards Air Force Base's Rocket Engine Test Facility) before being discharged in 1958. During his service, he secured an amateur radio license and a general radiotelephone operator license.[citation needed]

Later, inspired by a 1958 performance of the Bolshoi Ballet, he studied ballet in Los Angeles, supporting himself for a time as a professional dancer.[14] In 1963, he enrolled at the University of California, Berkeley, where he became involved in the psychoactive drug scene. He dropped out after a semester, took a technical job at KGO-TV, and began producing LSD in a small lab located in the bathroom of a house near campus; his makeshift laboratory was raided by police on February 21, 1965. He beat the charges and successfully sued for the return of his equipment.[15] The police were looking for methamphetamine but found only LSD, which was not illegal at the time as its classification as a Schedule I controlled substance in the U.S. did not occur until 1968.[16]

Stanley returned to Los Angeles to pursue the production of LSD. He used his Berkeley lab to buy 500 grams of lysergic acid monohydrate, the basis for LSD. His first shipment arrived on March 30, 1965, and he produced 300,000 hits (270 micrograms each) of LSD by May 1965; then he returned to the Bay Area.[citation needed]

In September 1965, Stanley became the primary LSD supplier to Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters. By this time, Sandoz LSD sold under the trade-name Delysid was hard to come by, as Sandoz halted LSD production in August 1965 after growing governmental protests at its proliferation among the general populace, which meant that "Owsley Acid" had become the new standard.[17][18] He was featured (most prominently his freak-out at the Muir Beach Acid Test in November 1965) in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test (1968), Tom Wolfe's book detailing the history of Kesey and the Merry Pranksters. Stanley attended the Watts Acid Test on February 12, 1966, with his new apprentice Tim Scully, and provided the LSD.[citation needed]

Stanley also provided LSD to the Beatles during filming of Magical Mystery Tour (1967),[19] and former Three Dog Night singer Chuck Negron has noted that Owsley and Leary gave Negron's band free LSD.[20]

Involvement with the Grateful Dead

[edit]Stanley met the members of the Grateful Dead during 1965.[21] He both financed them and worked with them as their first sound engineer.[22] Along with his close friend Bob Thomas, Stanley designed the band's iconic 'Steal Your Face' lightning bolt-skull logo.[2] The lightning bolt design came to him after seeing a similar design on a roadside advertisement: "One day in the rain, I looked out the side and saw a sign along the freeway which was a circle with a white bar across it. The top of the circle was orange, and the bottom blue. I couldn't read the name of the firm, and so was just looking at the shape. A thought occurred to me: if the orange were red and the bar across were a lightning bolt cutting across at an angle, then we would have a very nice, unique and highly identifiable mark to put on the equipment."[2]

During his time as the sound engineer for the Grateful Dead, Stanley started what became the long-term practice of recording the Dead while they rehearsed and performed. His initial motivation for creating what he dubbed his "sonic journals" was to improve his ability to mix the sound, but the fortuitous result was an extensive trove of recordings from the heyday of the San Francisco concert/dance scene in the mid-1960s.[23] Another reason for the first recordings was that Stanley had hearing damage in one ear from a swimming-pool diving accident when he was 19, and wanted a way to check himself.[24][25]

In addition to his large archive of Dead performances, Stanley made numerous live recordings of other leading 1960s and 1970s artists appearing in San Francisco, including Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen, New Riders of the Purple Sage, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Jefferson Airplane, early Jefferson Starship, Old & In the Way, Janis Joplin, Big Brother and the Holding Company, Taj Mahal, Santana, Miles Davis, the Flying Burrito Brothers, Jimi Hendrix, Johnny Cash, and Blue Cheer.[9]

Live albums recorded by Owsley Stanley include Bear's Choice by the Grateful Dead, Old & In the Way by the bluegrass group of the same name, Live at the Avalon Ballroom 1969 by the Flying Burrito Brothers, and Live at the Carousel Ballroom 1968 by Big Brother and the Holding Company with Janis Joplin. Also, a number of Grateful Dead archival releases, including several of the Dick's Picks and Dave's Picks series and other titles, were recorded by him. Additionally, the Bear's Sonic Journals series of live albums (see below) feature various musical artists recorded by Stanley.[citation needed]

Richmond LSD lab

[edit]Stanley and Scully built electronic equipment for the Grateful Dead until late spring 1966. At this point, Stanley rented a house in Point Richmond, Richmond, California. He, Scully, and Melissa Cargill (a skilled chemist and Cargill family scion who became Stanley's girlfriend following an introduction by Susan Cowper, a former girlfriend) set up a lab in the basement. The Point Richmond lab turned out more than 300,000 tablets (270 micrograms each) of LSD, dubbed "White Lightning". When LSD became illegal in California on October 6, 1966, Scully decided to set up a new lab in Denver, Colorado. The new lab was set up in the basement of a house across the street from the Denver Zoo in early 1967.[26]

In Denver, the trio was augmented by fellow Berkeley student Rhoney Gissen, who joined the manufacturing effort and began a relationship with Stanley (concurrent with Stanley's relationship with Cargill and Cargill's separate relationship with Jefferson Airplane bassist Jack Casady) that endured through the early 1970s; although they never married, Gissen would eventually take Stanley's surname. Stanley's scientific tutelage influenced Gissen's decision to return to her formal studies and pursue the profession of dentistry; their son, Starfinder, would go on to earn zoology and veterinary medicine degrees from Cornell University and the University of Pennsylvania.[27]

Legal trouble and continued involvement with the Grateful Dead

[edit]A psychedelic known as STP was distributed in the summer of 1967 in 20 mg tablets and quickly acquired a bad reputation (later research in normal volunteers showed that 20 mg was over six times the dose required to produce hallucinogenic effects, and its slow onset of action may have caused street users to take even more than a single tablet).[28] Stanley and Scully made trial batches of STP in 10 mg tablets and then of STP mixed with LSD in a few hundred yellow tablets, but soon ceased production of STP. Stanley and Scully produced about 196 grams of LSD in 1967, but 96 grams of that was confiscated by the police.[citation needed]

In late 1967, Stanley's lab at La Espiral, Orinda, California, was raided by police and he was found in possession of 350,000 doses of LSD and 1,500 doses of STP. His defense was that the illegal substances were for personal use, but he was found guilty and sentenced to three years in prison. The same year, Stanley officially shortened his name to "Owsley Stanley". After his release from prison, Stanley resumed working for the Grateful Dead as their live sound engineer. On January 31, 1970, at 3:00 a.m., 19 members of the Grateful Dead and crew were arrested for possession of a variety of drugs at a French Quarter hotel after returning from a concert at The Warehouse in New Orleans.[citation needed]

According to Rolling Stone magazine,[29] everyone in the band except Ron "Pigpen" McKernan and Tom Constanten—neither of whom used psychedelic drugs—was included in the arrest, along with several members of their retinue, including Stanley and some locals. Stanley was charged with illegal possession of narcotics, dangerous non-narcotics, LSD, and barbiturates. Another West Coast–based rock band, Jefferson Airplane, had been arrested two weeks earlier in the same situation. According to an article in the Baton Rouge State Times, Stanley identified himself to the police as "The King of Acid" and technician of the band. The 1970 Grateful Dead song "Truckin' " is based on the incident ("Busted, down on Bourbon Street / Set up, like a bowling pin / Knocked down, it gets to wearing thin / They just won't let you be").[30]

Stanley was confined to federal prison from 1970 to 1972, after a federal judge intervened and revoked his release from the 1967 conviction. Stanley took advantage of the opportunity in jail to learn the trade of metalwork and jewelry-making.[7]

Immediately following his release in the summer of 1972, Stanley resumed working for the Grateful Dead as a roadie and sound engineer. Since his portfolio had been delegated to as many as four sound engineers during his time in prison, he struggled to regain his past influence with the band and support staff. In a later interview with Dennis McNally, he opined that he received "just a taste" of his previous position: "I found on my release from jail that the crew, most of whom had been hired in my absence, did not want anything changed. No improvements for the sound, no new gear, nothing different on stage. They wanted to maintain the same old same old which under their limited abilities, they had memorized to the point where they could sleepwalk through shows. Bob Matthews, who had been mixing since my departure, did not want to completely relinquish the mixing desk, which was a total pain in the ass for me, since he was basically a studio engineer and no match for my live mixing ability." The situation was exacerbated by his disdain for the coarse language and deleterious drugs (most notably alcohol and cocaine) favored by the band's physically imposing roadies, many of whom perceived themselves as "macho cowboys", in contrast to Stanley's diminutive stature and scholarly demeanor.[citation needed]

The tensions culminated in a logistical mishap at an October 1972 concert at Vanderbilt University, at which students recruited by Stanley to deputize for an absent Matthews absconded with half of the band's PA system, resulting in a fellow employee throwing Stanley into a water cooler. The altercation led Stanley to request the formal codification of his perceived managerial power over the equipment staff, including unprecedented hire/fire privileges.[31]

Although Stanley stopped touring with the Grateful Dead following their refusal of his demands, he continued to be employed by the band. In 1973, he served as lead designer of the band's Wall of Sound, collaborating with Dan Healy and Mark Raizene, as well as Rick Turner and John Curl of Alembic, to design the ground-breaking sound reinforcement system.[32] During that period, Stanley also assisted Phil Lesh in salvaging the technically deficient recordings assembled for Steal Your Face (1976), a poorly-received live album culled from the final October 1974 pre-hiatus shows at Winterland Ballroom.[33] Following the hiatus, Stanley returned as Lesh's personal roadie for "a couple of tours" in the late 1970s, although personality conflicts with other crew members once again precipitated his departure.[34]

Post–Grateful Dead career

[edit]In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Stanley briefly served as the live mixing engineer for Robert Hunter and Jefferson Starship. From 1974 to 1981, he also grew and sold cannabis from his garden in Fairfax, California, but the profits from this endeavor proved to be far less remunerative than his earlier work in clandestine chemistry. Stanley moved to Australia in 1982, and frequently returned to the United States to sell his jewelry (which commanded high prices) on Grateful Dead tours. He retained backstage access during this period, and his clientele included such notable figures as Keith Richards.[5]

Stanley's level of access to the group's inner echelon (including complimentary food from the band's caterers) was somewhat controversial among the band's employees, with one staffer opining that "he had the sales tactics of a Mumbai street peddler"; on one occasion, Garcia and Weir were forced to intervene when Stanley provoked Chelsea Clinton's Secret Service detail as he attempted to conduct business with the then-First Daughter.[35]

Notwithstanding his tour activities, Stanley made his first public appearance in decades at the Australian ethnobotanical conference Entheogenesis Australis in 2009, giving three talks during his time in Melbourne.[36][37]

Personal life and death

[edit]Stanley believed a "thermal cataclysm" related to climate change would soon render the Northern Hemisphere largely uninhabitable, and moved to Australia in 1982. He became a naturalized Australian citizen in 1996. Stanley lived with his wife Sheilah (a former clerk in the Grateful Dead's ticket office) in the bush of Tropical North Queensland, where he worked to create sculpture and wearable art.[6][38]

From at least the mid-1960s until his death, Stanley practiced and advocated an all-meat diet, believing that humans are naturally carnivorous.[6] He argued that rare red meat was a complete food and that a diet of such is optimal for human health and longevity. He held many radical opinions on biology and nutrition. He argued that the body could not store protein or fat as adipose tissue, but would instead be simply excreted if consumed in excess, and that only consumption of carbohydrates and sugars could make someone obese. He also theorized that diabetes was not technically a disease but actually the term for the damage wrought by insulin, and that adopting a zero carb diet would treat this so-called disease.[citation needed]

Stanley died after a car accident in Australia on Saturday, March 12, 2011,[7] not Sunday, March 13, as reported in most publications[9][10][11][39][40] (a widely propagated error stemming from the Monday release to the press of the initial family statement, which was written on Sunday, stating he "died yesterday"). The statement released on behalf of Stanley's family said the car crash occurred near his home, on a rural stretch of highway near Mareeba, Queensland.[citation needed]

His ashes were placed on the soundboard at the celebration of the Grateful Dead's 50th anniversary at the Fare Thee Well: Celebrating 50 Years of the Grateful Dead shows in Chicago, on July 3–5, 2015.[41]

Owsley Stanley Foundation

[edit]Shortly before his death, Stanley was in the process of curating and releasing the first of a planned series of concert recordings, to be called "Bear's Sonic Journals". The first of these releases was set to be Live at the Carousel Ballroom 1968 by Big Brother and the Holding Company featuring Janis Joplin.[42] After he died, the album was finished and released by Columbia / Legacy Records, under the supervision of his family and some close friends.[citation needed]

Subsequently, a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization known as the Owsley Stanley Foundation was founded, dedicated to restoring and preserving the archive of Stanley's recordings, which he called his "sonic journals".[43][44][45][46][47] Through the work of the Owsley Stanley Foundation, some of these concert recordings have been released as a series of live albums.[citation needed]

Bear's Sonic Journals

[edit]- Bear's Sonic Journals Presents: Live at the Carousel Ballroom 1968 – Big Brother and the Holding Company featuring Janis Joplin – March 12, 2012[a]

- Bear's Sonic Journals: Never the Same Way Once – Doc Watson and Merle Watson – June 23, 2017[48][49][50]

- Bear's Sonic Journals: Fillmore East, February 1970 – The Allman Brothers Band – August 10, 2018[51]

- Bear's Sonic Journals: Before We Were Them – Jorma Kaukonen and Jack Casady (i.e. Hot Tuna) – January 18, 2019[52]

- Bear's Sonic Journals: Dawn of the New Riders of the Purple Sage – New Riders of the Purple Sage – January 17, 2020[53]

- Bear's Sonic Journals: Found in the Ozone – Commander Cody and His Lost Planet Airmen – July 24, 2020[54]

- Bear's Sonic Journals: That Which Colors the Mind – Ali Akbar Khan – December 18, 2020[55][56][57][58][59][60]

- Bear's Sonic Journals: Merry-Go-Round at the Carousel – Tim Buckley – June 4, 2021[61][62][63][64][65]

- Bear's Sonic Journals: At the Carousel Ballroom, April 24, 1968 – Johnny Cash – October 29, 2021[66][67][68][69][70][71]

- Bear's Sonic Journals: The Foxhunt – The Chieftains – September 2, 2022[72][73][74]

- Bear's Sonic Journals: Sing Out! – various artists – February 23, 2024[75]

- Bear's Sonic Journals: You're Doin' Fine – John Hammond – November 22, 2024

- Notes:

In popular culture

[edit]In literature

[edit]- Owsley's association with Ken Kesey and the Grateful Dead is described in Tom Wolfe's The Electric Kool Aid Acid Test (1968).

- Stanley's incarceration is lamented in Hunter S. Thompson's Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (1971) as one of the many signs of the death of the 1960s.[76]

In music

[edit]- A newspaper headline identifying Stanley as an "LSD Millionaire" ran in the Los Angeles Times the day before the state of California, on October 6, 1966, criminalized the drug. The headline inspired the Grateful Dead song "Alice D. Millionaire".[21]

- Stanley is mentioned by his first name in the song "Who Needs the Peace Corps?" by Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, which first appeared on the band's album We're Only in It for the Money (1968) ("I'll go to Frisco, buy a wig and sleep on Owsley's floor.").[77][78][79][80][81]

- Stanley is referred to in Jefferson Airplane's song "Mexico" on the Early Flight (1974) album.

- Stanley is the subject of Spectrum's song "Owsley", which appears on their 1997 Forever Alien album and its precursor EP Songs For Owsley (1996). The latter was titled in tribute to Stanley.

- Stanley is the subject of The Masters Apprentices' song "Our Friend Owsley Stanley 3", which appears on their 1971 album Master's Apprentices.

- The Steely Dan song "Kid Charlemagne", from the album The Royal Scam (1976), is based on Stanley's activities as a drug manufacturer.[82][83][84][85]

- Stanley is mentioned in the title of Sujoy Sarkar's debut album Sitting at Strawberry Fields Cause I Met Owsley on the Way (2020).[86]

See also

[edit]- Counterculture of the 1960s

- Casey William Hardison

- History of lysergic acid diethylamide

- William Leonard Pickard

- Psychonautics

- Nicholas Sand

- Tim Scully

- The Brotherhood of Eternal Love

- The Sunshine Makers

References

[edit]- ^ Greenfield, Robert (March 14, 2011) [March 14, 2011]. "Owsley Stanley: The King of LSD". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved August 28, 2024.

- ^ a b c "GD Logo". thebear.org. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ McDougal, Dennis (2020). Operation White Rabbit: LSD, the DEA, and the Fate of the Acid King. Simon and Schuster. p. 45. ISBN 9781510745384.

- ^ Nicholas von Hoffman (October 17, 1967). "113 Cong. Rec. (Bound) - November 6, 1967". GovInfo.gov. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 31190. Retrieved June 22, 2023.

Sandoz, a Swiss pharmaceutical company, ceased making acid available when it became illegal, but another brand has taken its place, and today Owsley acid is considered the best available. It is so named after the middle name of Augustus Owsley Stanley, a young man in his early thirties who is referred to in the San Francisco papers as the 'Acid King.'

- ^ a b Selvin, J. "For the unrepentant patriarch of LSD, long, strange trip winds back to Bay Area". San Francisco Chronicle, July 12, 2007.

- ^ a b c Greenfield, Robert (March 14, 2011). "Owsley Stanley: The King of LSD". Rolling Stone.

- ^ a b c d e Margalit Fox (March 15, 2011). "Owsley Stanley, Artisan of Acid, Is Dead at 76". The New York Times. p. B18.

- ^ Forte, Robert (1999). Timothy Leary: Outside Looking In. Park Street Press. p. 276. ISBN 0892817860.

- ^ a b c Carlson, Michael (March 15, 2011). "Owsley Stanley Obituary". The Guardian. Retrieved November 25, 2014.

- ^ a b "Owsley 'Bear' Stanley Dies in Car Accident", jambands.com, March 13, 2011

- ^ a b Greenfield, Robert (March 14, 2011). "Owsley Stanley: The King of LSD". Rolling Stone. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Owsley Stanley, counterculture producer of LSD, dies at 76 – KansasCity.com

- ^ Clark, Charlie (November 22, 2016). "Our Man in Arlington".

- ^ Owsley Stanley blog posting. 17 March 2006.

- ^ Perry, Charles (1984). The Haight-Ashbury: A History (PDF). Random House. ISBN 0-394-41098-X. Retrieved March 24, 2011.

- ^ United States Congress House Committee on Interstate and Foreign Commerce Subcommittee on Public Health and Welfare (1968). Increased Controls Over Hallucinogens and Other Dangerous Drugs. U.S. Government Printing Office. Archived from the original on July 13, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2021.

- ^ "Sandoz Pharmaceuticals". March 9, 2021.

- ^ "LSD - My Problem Child".

- ^ Fraser, Andrew (March 14, 2011). "Owsley 'Bear' Stanley dies in North Queensland car crash". The Australian. News Limited. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ Freeman, Paul (August 15, 2012). "The dark, one-dog night of Chuck Negron". San Jose Mercury News.

- ^ a b Troy, Sandy, Captain Trips: A Biography of Jerry Garcia (New York: Thunder's Mouth Press, 1994). Acid Tests pp. 70–1, 76, 85; LSD Millionaire p. 99.

- ^ Pareles, Jon (August 10, 1995). "Jerry Garcia of Grateful Dead, Icon of 60's Spirit, Dies at 53". The New York Times. Retrieved March 11, 2009.

- ^ Melvin Backstrom (2018). The Grateful Dead and their world: popular music and the avant-garde in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1965-1975 (PhD thesis). McGill University.

- ^ "Bear: The Life and Times of Augustus Owsley Stanley III – B&N Readouts". July 12, 2018.

- ^ "Internet Archive Forums: Re: Owsley question".

- ^ Tim Scully Scully's Denver Lab(s)

- ^ "About Dr. Starfinder Stanley". January 15, 2017.

- ^ Snyder, Solomon; Faillace, Louis; Hollister, Leo (October 6, 1967). "2,5-Dimethoxy-4-methyl-amphetamine (STP): A New Hallucinogenic Drug". Science. 158 (3801). American Association for the Advancement of Science: 669–670. Bibcode:1967Sci...158..669S. doi:10.1126/science.158.3801.669. PMID 4860952. S2CID 24065654. Archived from the original on April 30, 2018. Retrieved September 10, 2016.

- ^ "New Orleans Cops & the Dead Bust". Rolling Stone. No. 53. March 6, 1970.

- ^ Lifton, Dave (January 31, 2015). "45 Years Ago: The Grateful Dead's Infamous 'Truckin' Drug Bust". Ultimate Classic Rock. Retrieved April 16, 2017.

- ^ Greenfield, Robert (November 15, 2016). Bear: The Life and Times of Augustus Owsley Stanley III. Macmillan. ISBN 9781466893115 – via Google Books.

- ^ Osborne, Luka (April 22, 2021). "Remembering the Grateful Dead's Wall of Sound: an absurd feat of technological engineering". happymag.tv. Happy Media PTY Limited. Retrieved August 3, 2022.

- ^ Light Into Ashes (July 1, 2010). "Grateful Dead Guide: Bear at the Board".

- ^ Greenfield, Robert (November 15, 2016). Bear: The Life and Times of Augustus Owsley Stanley III. Macmillan. ISBN 9781466893115 – via Google Books.

- ^ Greenfield, Robert (November 15, 2016). Bear: The Life and Times of Augustus Owsley Stanley III. Macmillan. ISBN 9781466893115 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Entheogenesis Australis". In 2009, around 500 participants were addressed by…the legendary – but reclusive – Owsley 'Bear' Stanley, in his first public appearance in decades.

- ^ "History". Entheogenesis Australis. Retrieved October 23, 2023.

- ^ "Remembering Owsley "Bear" Stanley | Grateful Dead". Archived from the original on September 18, 2018. Retrieved May 30, 2017.

- ^ "Psychedelic icon Owsley Stanley dies in Australia". Thomson Reuters. March 13, 2011.

- ^ "Owsley Stanley". The Daily Telegraph. 19 March 2011.

- ^ "Music News - Concert Reviews - JamBase". JamBase. July 8, 2015. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ Columbia/Legacy Recordings (March 13, 2012). "Columbia/Legacy Recordings Releasing the First of "Bear's Sonic Journals": Big Brother & the Holding Company Featuring Janis Joplin Live at the Carousel Ballroom 1968, Recorded & Produced by Owsley Stanley ("Bear")". PR Newswire. Retrieved July 30, 2024.

- ^ "About the Owsley Stanley Foundation". Owsley Stanley Foundation. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Bannerman, Mark (March 23, 2019). "Owsley Stanley's Acid Trips Helped Define the Sound of the 1960s, but His Recordings Are Just as Important". ABC News. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Jarnow, Jesse (December 5, 2019). "Owsley Stanley's 'Sonic Journals': Inside the Tape Vault of a Psychedelic Legend". Rolling Stone. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "Bear at the Board". Grateful Dead Guide. July 1, 2010. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Budnick, Dean (November 18, 2021). ""I'll Take My Chances on an Acid-Soaked Jimi Hendrix": Seeing Sound with Johnny Cash and the Owsley Stanley Foundation". Relix. Retrieved November 19, 2021.

- ^ Moses, Desiré (July 26, 2017). "Doc & Merle Watson: Play 'Never the Same Way Once' on New Box Set". The Bluegrass Situation. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "First Doc & Merle Watson Box Set Released". Cybergrass. May 23, 2017. Archived from the original on July 12, 2017. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Kahn, Andy (May 23, 2017). "Owsley Stanley Foundation Announces Doc & Merle Watson Live Box Set". JamBase. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Bernstein, Scott (July 19, 2018). "Previously Unreleased Allman Brothers Band Recordings from February 1970 Fillmore East Run Coming". JamBase. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ "Before We Were Them". Owsley Stanley Foundation. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Collette, Doug (February 17, 2020). "Bear's Sonic Journals: Dawn of the New Riders of the Purple Sage". Glide Magazine. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Tamarkin, Jeff (November 12, 2020). "Commander Cody & His Lost Planet Airmen – Bear's Sonic Journals: Found in the Ozone". Relix. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ "That Which Colors the Mind". Owsley Stanley Foundation. Retrieved November 27, 2020.

- ^ Patel, Madhu (October 29, 2020). "Owsley Stanley Foundation to Release Rare Performance by Ali Akbar Khan from 1970". India Post. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ Kureshi, Anisa (December 8, 2020). "Smoke in a Bottle: That Which Colors the Mind". India Currents. Retrieved December 11, 2020.

- ^ Collette, Doug (December 14, 2020). "Bear's Sonic Journals: That Which Colors the Mind – Ali Akbar Khan / Indranil Bhattacharya / Zakir Hussain". Glide Magazine. Retrieved December 24, 2020.

- ^ Tamarkin, Jeff (January 25, 2021). "Global Beat: Zakir Hussain Revisits a Historic Family Dog Summit". Relix. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ Qureshi, Bilal (January 23, 2021). "When the Giants of Indian Classical Music Collided with Psychedelic San Francisco". NPR. Retrieved February 21, 2022.

- ^ "Merry-Go-Round at the Carousel". Owsley Stanley Foundation. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- ^ McNally, Dennis (May 11, 2021). "Owsley Stanley Foundation to Release Landmark Tim Buckley Live Recording". Grateful Web. Retrieved May 23, 2021.

- ^ Browne, David (June 11, 2021). "Tim Buckley Lets His Freak Flag Fly on Live LP 'Merry-Go-Round at the Carousel'". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 11, 2021.

- ^ Apice, John (June 8, 2021). "Review: Tim Buckley "Merry-Go-Round at the Carousel – Live"". Americana Highways. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- ^ Collette, Doug (June 9, 2021). "Tim Buckley Displays Adventurous Spirit Via 'Bear's Sonic Journals: Merry-Go-Round at the Carousel June 1968' (Album Review)". Glide Magazine. Retrieved February 19, 2022.

- ^ Blistein, Jon (June 24, 2021). "New Johnny Cash Live Album, 'At the Carousel Ballroom' Captures Country Star in the Counterculture". Rolling Stone. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ Moore, Sam (June 24, 2021). "A Johnny Cash Live Album from 1968 Is Finally Set to Be Released". NME. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ Todd, Nate (June 24, 2021). "Previously Unreleased Johnny Cash Live Album Recorded by Owsley Stanley Due in September". JamBase. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ Broerman, Michael (June 24, 2021). "Johnny Cash 1968 Carousel Ballroom Live Bootleg Recorded by Owsley Headed for Release". Live for Live Music. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ Blake, Logan (June 24, 2021). "Johnny Cash's Previously Unreleased Live Album from 1968 to Be Unearthed". Spin. Retrieved June 25, 2021.

- ^ Paumgarten, Nick (November 1, 2021). "When the Man in Black Met the Guys in Tie-Dye". The New Yorker. Retrieved November 2, 2021.

- ^ McNally, Dennis (July 26, 2022). "Owsley Stanley Foundation to Release Early Chieftains Live Recordings". Grateful Web. Retrieved July 26, 2022.

- ^ "Bear's Sonic Journals: The Foxhunt, The Chieftains Live in San Francisco 1973 & 1976 to Be Released". The Sound Cafe. July 22, 2022. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- ^ Broerman, Michael (September 1, 2022). "Ireland's The Chieftains Land on U.S. Soil in Latest 'Bear's Sonic Journals' Release". Live for Live Music. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ Kahn, Andy (January 4, 2024). "Owsley 'Bear' Stanley's Final Live Recording Featuring Members of Grateful Dead Set for Release". JamBase. Retrieved January 8, 2024.

- ^

Thompson, Hunter S. (November 6, 2003). The great shark hunt: strange tales from a strange time. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9780743250450. Retrieved April 21, 2011.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ "1960s LSD Figure Owsley Stanley Dies In Crash – Entertainment News Story – WISC Madison". Archived from the original on March 17, 2011.

- ^ "millionaire". chetanmohakar.com. Archived from the original on January 30, 2019.

- ^ "R.I.P. Owsley – Viceland Today". Archived from the original on July 17, 2011.

- ^ NME.COM. "Jimi Hendrix inspiration and LSD producer Owsley Stanley dies". NME.COM. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ "Owsley Stanley Obituary - Owsley Stanley Funeral - Legacy.com". Legacy.com. March 15, 2011. Retrieved December 31, 2015.

- ^ "Complete transcript of Donald Fagen and Walter Becker in a BBC-Online Chat, March 4, 2000". BBC. March 4, 2000. Archived from the original on April 13, 2009. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ Kamiya, Gary (March 14, 2000). "Sophisticated skank". Salon. Retrieved January 6, 2013.

- ^ Marcus Singletary. "Steely Dan: Kid Charlemagne". Jazz.com. Archived from the original on June 10, 2012. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ Pershan, C., "Kid Charlemagne: A Close Reading Of Steely Dan's Ode to Haight Street's LSD King" Archived 2016-03-17 at the Wayback Machine, SFist, July 20, 2015.

- ^ Britto, David (November 28, 2020). "Producer Sujoy Sarkar Drops Enigmatic Debut Album 'Sitting At Strawberry Fields Cause I Met Owsley on the Way'". Rolling Stone India. Retrieved April 12, 2021.

Sources

[edit]- Lee, Martin A; Bruce Shlain (1986). Acid Dreams: The Complete Social History of LSD: The CIA, the Sixties, and Beyond. Grove Press. ISBN 0-8021-3062-3.

- McCleary, John Bassett (2004). The Hippie Dictionary: A Cultural Encyclopedia of the 1960s and 1970s. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press. ISBN 1-58008-547-4.

- Wolfe, Tom (1968). The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Forte, Robert (1999). Timothy Leary: Outside Looking In. Park Street Press. pp. 270–278. ISBN 0892817860.

- Greenfield, Robert (2016). Bear: The Life and Times of Augustus Owsley Stanley III. Thomas Dunne Books. ISBN 978-1-250-08121-6.

External links

[edit]- Owsley's website

- "For the unrepentant patriarch of LSD, long, strange trip winds back to Bay Area" San Francisco Chronicle July 12, 2007

- Obituary from Reuters.com

- Celebstoner.com report of Owsley Stanley's Death

- Owsley Stanley discography at Discogs

- Two Robots Talking: Episode 5: The Psychedelic Maestro: Owsley, LSD, & the Grateful Dead Sound Revolution

- 1935 births

- 2011 deaths

- American audio engineers

- American chemists

- American emigrants to Australia

- American psychedelic drug advocates

- Chemists from Kentucky

- Engineers from Kentucky

- Grateful Dead

- Hippies

- Lysergic acid diethylamide

- Military personnel from Kentucky

- Naturalised citizens of Australia

- People from Far North Queensland

- People from Orinda, California

- Road incident deaths in Queensland