Paulina Luisi

Paulina Luisi | |

|---|---|

Luisi in 1921 | |

| Born | Paulina Luisi Janicki 1875 |

| Died | 1950 (aged 74–75) |

| Occupation(s) | Physician, teacher, activist |

Paulina Luisi Janicki (1875–1950) was a leader of the feminist movement in Uruguay. In 1909, she became the first Uruguayan woman to earn a medical degree and was a firm advocate of sex education in schools. She represented Uruguay in international women's conferences and traveled throughout Latin America and Europe. She also represented Uruguay at the League of Nations, advocating for the rights of women and children and pushing for an end to sex trafficking. Her work has had a lasting effect on women in the Americas.

Early life and education

[edit]Paulina Luisi was born in Colón, Argentina in 1875.[1] Her mother, Maria Teresa Josefina Janicki, was a women's suffrage activist of Polish descent and her father, Angel Luisi, was a socialist and educator believed to be of Italian ancestry.[2][3] Shortly after her birth, the family moved to Uruguay. Luisi also had two sisters: Clotilde Luisi, who was the first female lawyer in Uruguay, and Luisa Luisi, who was a famous poet.[4][5]

Luisi earned a teaching degree in 1890 and became the first woman in Uruguay to earn a bachelor's degree in 1899. In 1908, she became the first woman to graduate from the Medical School of the University of the Republic of Uruguay, and soon after she became the head of the gynecology clinic of the university's Faculty of Medicine.[6] At the time Luisi was starting her medical career, there were only four female doctors in Uruguay, compared to 305 male doctors. As more women joined the medical field, however, the number of female physicians started to rise.[7]

Luisi was introduced to the Latin American feminist movement during her time at university, with Argentine feminist Petrona Eyle writing to her to recruit her to join her organization, Universitarias Argentinas ('Argentine Association of University Women'). In a letter dated May 1, 1907, Eyle encouraged Luisi and her female colleagues in the university to form an Uruguayan branch of the Universitarias, stating that “although there aren’t many of you now, you will always be the nucleus around which others will come together.” The Uruguayan branch of the Universitarias was founded in 1907.[8]

Activism and career

[edit]Early activism

[edit][Femnism demonstrates that] woman is something more than material created to serve and obey man like a slave, that she is more than a machine to produce children and care for the home; that women have feelings and intellect; that it is their mission to perpetuate the species and this must be done with more than the entrails and the breasts; it must be done with a mind and a heart prepared to be a mother and an educator; that she must be the man’s partner and counselor not his slave.

During the 1910s, Luisi took part in numerous conferences and other activities with the aim of advancing the feminist movement both in Uruguay and abroad.[17] In 1910, she participated in the Universitarias-organized Congreso Femenino (lit. 'Women's Congress') held in Buenos Aires. The conference was attended by over 200 women from Argentina, Uruguay, Peru, Paraguay, and Chile. While there, she became acquainted with prominent Argentine feminists such as Alicia Moreau de Justo and Cecilia Grierson, as well as other future leaders of the feminist movement in Latin America.[8] Later, she traveled to Europe, where became acquainted with members of the French feminist movement such as Avril de Sainte-Croix, president of the Moral Unity Committee of the International Council of Women, and Julie Siegfried, president of the National Council of French Women.[9]

In 1915, Luisi helped to found the Pan-American Women’s Auxiliary, which met at the same time as the Second Pan-American Scientific Congress in Washington, D.C. The Auxiliary, headed by the wives of high-ranking U.S. officials, advocated for the "social and economic betterment " of women and children.[11] Then in 1916, Luisi founded the Consejo Nacional de Mujeres del Uruguay (CONAMU, lit. 'National Women's Council of Uruguay') along with Isabel Pinto de Vidal and Francisca Beretervide.[12] She served as the primary editor of the CONAMU bulletin Acción Femenina (lit. 'Feminine Action'), which primarily focused on topics concerning women's values and equality.[9] She also gave the keynote address before the First Pan-American Child Congress in 1916, emphasizing the importance of democracy and women's rights, including the right to vote, in the Americas. While there, she introduced several resolutions advocating for sex education and public health.[13]

Luisi also began advocating for working-class women around this time. In 1918, she assisted in the creation of the Unión Nacional de Telefonistas (lit. 'Telephone Operators Union'), the first women's union in Uruguay, and intervened on their behalf to reduce workloads by decreasing the number of phone lines at the telephone company Montelco from 100 to 80. The intervention failed, with the number of phone lines going up between 1918 and 1922.[15]

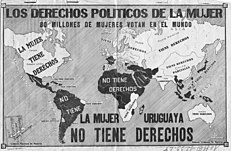

In 1919, Luisi helped to found the Alianza de Mujeres para los Derechos Femeninos (lit. 'Women's Alliance for Women's Rights'). The Alianza pressured elected officials to grant women various political rights.[14] The Alianza worked closely with Deputy Alfeo Brum to get the General Assembly to pass a bill authorizing women’s suffrage at the municipal level so that women could fulfill their "legitimate social duty of rendering service to the different domains of public welfare." The bill did not pass, and with suffrage stalled, the Alianza expanded its agenda to include women’s economic and civil rights.[16]

League of Nations work on sex trafficking

[edit]Luisi was strongly opposed to sex work, viewing it as a degrading "social evil." However, she also saw it as a product of economic hardship and saw the correlation between prostitution and low wages. The sex trade in general was seen as a growing problem in Latin America and around the world, with many women being forced to participate gainst their will.[18] In 1919, Luisi delivered a well-known lecture at the University of Buenos Aires titled "The White Slave Trade and the Problem of Reglementation." Not long after the conference, the Argentine-Uruguayan Abolitionist Committee was formed. She also collaborated with the Municipal Council of Buenos Aires in 1919 to outlaw brothels and provide work opportunities, legal protection, and hostels for sex workers seeking to leave the trade.[9]

Luisi worked extensively with the League of Nations' Committee on the Traffic of Women and Children, serving as the Uruguayan delegate and helping to ratify the League of Nations Convention for the Suppression of the Traffic in Women and Children in Uruguay in 1921.[18][19] She also helped to pass the Children's Code in 1934 in collaboration with the Uruguayan National Council of Women, which placed the responsibility for protecting children on the state while also granting care and social protections for pregnant women and tackling problems stemming from illegitimate births.[9]

Later activism

[edit]In her later years, Luisi's feminist activism began to take the form of radio broadcasting. During the 1930s, she hosted Radio Femenina, an "all-woman" radio station in Uruguay.[20] On air, Luisi urged feminists to remain active, arguing that women could make a difference acting as "mediators and peacemakers."[21] Luisi adopted the nickname Abuela (lit. 'Grandmother') while on air, giving her a sense of authenticity and authority that resonated with women in Uruguay. A milestone in Luisi's radio career occurred in 1942, when she encouraged women to vote in the 1942 elections to prove that women were worthy of citizenship.[22]

Luisi's belief in sex education, first enumerated in 1916, also became a more prominent part of her later advocacy.[13] She spoke extensively about its importance from the 1930s to the 1950s, positing that sex education would help foment responsibility and ethical behavior. Her suggestions earned her the label of "anarchist" and "revolutionary" from some. Nevertheless, in 1944, many of her suggestions for sexual education were incorporated into the Uruguayan public school system. In her 1950 book Pedagogia y Conducta Sexual (lit. 'Pedagogy and Sexual Behavior'), she "defined sex education as the pedagogic tool to teach the individual subject to sexual drives to the will of an instructed, conscientious, responsible intellect."[9][23]

Death and legacy

[edit]In 1947, the Primer Congreso Interamericano de Mujeres (lit. 'First Inter-American Women’s Conference') in Guatemala paid tribute to Luisi, recognizing her as the "mother" of inter-American feminism. Luisi died in Montevideo three years later on 16 July, 1950. Many of her papers remain in various archives across Montevideo.[24] She is remembered by historian Estela Ibarburu as "a person who marked a milestone in the process of women's empowerment."[4]

Views

[edit]

Luisi is strongly associated with the feminist movement in Latin America.[1] Her feminist views were influenced by figures within the Western liberal tradition, including Olympe de Gouges, the writer of the Declaration of the Rights of Woman and Josephine Butler, the 19th-century English moral reformer.[25] Butler's fight against the Contagious Disease Act of 1864 and her foundation of the International Abolitionist Federation (IAF) in Geneva, Switzerland to curb the so-called "white slave trade" was particularly inspiring to Luisi.[9]

In addition to fighting for women’s rights in Uruguay, Luisi aspired to create a pan-American feminist movement that would benefit all countries in the Americas.[26] Luisi traveled to the United States with the hope of having American feminists help develop pan-American feminism, but she emerged disappointed in American women’s disdain for Latin American feminists. However, with the outbreak of World War II, she returned to her earlier pan-American stance, once again advocating for "sisterhood" between the two groups.[27]

Luisi has also been associated with the moral reform movement. She espoused an ideal of "moral unity," which was characterized by its opposition to sex work and the spread of venereal diseases, as well as its general concern with elevating the role of women in society. She was also a self-identified socialist, calling for individual social responsibility and a "collective social consciousness."[9]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Marino 2019, p. 8

- ^ Mamolea, Andrei (11 May 2023). "The Role of International Law in Paulina Luisi's Activism". Portraits of Women in International Law: New Names and Forgotten Faces?. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 444–454. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198868453.003.0038. ISBN 978-0-19-886845-3.

- ^ Marino 2013, p. 38

- ^ a b Ibarburu, Estela (May 2014). "La vida y obra de Paulina Luisi" [The life and work of Paulina Luisi] (PDF). Temas. 5 (5/6): 143–157. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ Marino 2019, pp. 15-16

- ^ Birn, Anne-Emanuelle; Pollero, Raquel (19 April 2023). "Public Health in Uruguay, 1830–1940s". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.690. ISBN 978-0-19-936643-9.

- ^ Lavrin 1995, p. 106

- ^ a b c Ehrick 2005, p. 96

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Little, Cynthia Jeffress (1975). "Moral Reform and Feminism: A Case Study". Journal of Interamerican Studies and World Affairs. 17 (4): 386–397. doi:10.2307/174949. ISSN 0022-1937.

- ^ Luisi, Paulina (1917). "Montevideo: El Siglo Ilustrado" [Montevideo: The Enlightened Century]. Acción Femenina.

- ^ a b Marino 2019, pp. 19-20

- ^ a b Oldfield, Sybil (2003). International Woman Suffrage: October 1916-September 1918. London; New York: Taylor & Francis. p. 279. ISBN 0-415-25739-5. OCLC 50301382.

- ^ a b c Marino 2019, p. 14

- ^ a b Marino 2019, p. 21

- ^ a b Yael, Dina; Darré, Silvana (14 December 2020). "El triunfo de las señoritas telefonistas: El primer sindicato de mujeres del Uruguay y el impacto de la huelga de 1922" [The triumph of the telephone operators - The first women's union in Uruguay and the impact of the 1922 strike]. Zona Franca (in Spanish) (28): 270–302. doi:10.35305/zf.vi28.166. ISSN 2545-6504.

- ^ a b Asunción 1995, pp. 332-333

- ^ [8][9][11][12][13][14][15][16]

- ^ a b Rodríguez García, Magaly (2012). "The League of Nations and the Moral Recruitment of Women". International Review of Social History. 57 (S20): 97–128. doi:10.1017/S0020859012000442. ISSN 0020-8590.

- ^ Marino 2019, pp. 76-77

- ^ Ehrick, Christine (22 August 2017). "Women, Politics, and Media in Uruguay, 1900–1950". Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Latin American History. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199366439.013.303. ISBN 978-0-19-936643-9.

- ^ Ehrick 2015, p. 107

- ^ Ehrick 2015, p. 112-114

- ^ Luisi, Paulina (1950). Pedagogia y Conducta Sexual [Pedagogy and Sexual Behavior]. Montevideo. p. 82-83.

- ^ Marino 2019, pp. 227-229

- ^ Marino 2013, p. 41

- ^ Marino 2019, pp. 14-15

- ^ Marino 2013, p. 24

Sources and further reading

[edit]- Ehrick, Christine (2005). The Shield of the Weak: Feminism and the State in Uruguay, 1903-1933. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 978-0-8263-3470-1.

- Ehrick, Christine (2015). Radio and the Gendered Soundscape: Women and Broadcasting in Argentina and Uruguay, 1930–1950. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781139941945. ISBN 978-1-139-94194-5.

- Lavrin, Asunción (1995). Women, Feminism, and Social Change in Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay, 1890-1940. Lincoln (Neb.): University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-2897-X.

- Marino, Katherine (2013). La Vanguardia Feminista: Pan-American Feminism and the Rise of International Women's Rights, 1915-1946 (PDF) (PhD thesis). Stanford: Stanford University. Retrieved 24 September 2024.

- Marino, Katherine (2019). Feminism for the Americas: The Making of an International Human Rights Movement. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-4696-4969-6.

- 1875 births

- 1930 deaths

- Uruguayan feminists

- Uruguayan suffragists

- Socialist feminists

- Argentine emigrants to Uruguay

- Uruguayan people of Italian descent

- Uruguayan people of Polish descent

- 20th-century Uruguayan women politicians

- 20th-century Uruguayan politicians

- 20th-century Uruguayan physicians

- Uruguayan women physicians

- Uruguayan gynaecologists