Macular edema

| Macular edema | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Macular oedema,[1] familial macular edema |

| |

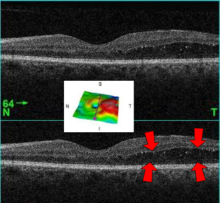

| A 61-year-old man with medical history of type 2 diabetes that presents a macular edema, evidenced by an OCT (the edema marked with arrows). The central image is a 3D reconstruction of the retinal thickness (the edema is coloured in red). | |

| Specialty | Ophthalmology |

Macular edema occurs when fluid and protein deposits collect on or under the macula of the eye (a yellow central area of the retina) and causes it to thicken and swell (edema). The swelling may distort a person's central vision, because the macula holds tightly packed cones that provide sharp, clear, central vision to enable a person to see detail, form, and color that is directly in the centre of the field of view.

Cause

[edit]The causes of macular edema are numerous and different causes may be inter-related.

- It is commonly associated with diabetes. Chronic or uncontrolled diabetes type 2 can affect peripheral blood vessels including those of the retina which may leak fluid, blood and occasionally fats into the retina causing it to swell.[2]

- Age-related macular degeneration may cause macular edema. As individuals age there may be a natural deterioration in the macula which can lead to the depositing of drusen under the retina sometimes with the formation of abnormal blood vessels.[3]

- Replacement of the lens as treatment for cataract can cause pseudophakic macular edema. (‘pseudophakia’ means ‘replacement lens’) also known as Irvine-Gass syndrome The surgery involved sometimes irritates the retina (and other parts of the eye) causing the capillaries in the retina to dilate and leak fluid into the retina. Less common today with modern lens replacement techniques.[4]

- Chronic uveitis and intermediate uveitis can be a cause.[5]

- Blockage of a vein in the retina can cause engorgement of the other retinal veins causing them to leak fluid under or into the retina. The blockage may be caused, among other things, by atherosclerosis, high blood pressure and glaucoma.[6]

- A number of drugs can cause changes in the retina that can lead to macular edema. The effect of each drug is variable and some drugs have a lesser role in causation. The principal medication known to affect the retina are:- latanoprost, epinephrine, rosiglitazone, timolol and thiazolidinediones among others.[7][8]

- A few congenital diseases are known to be associated with macular edema for example retinitis pigmentosa and retinoschisis.[2]

Diagnosis

[edit]Classification

[edit]

Cystoid macular edema (CME) involves fluid accumulation in the outer plexiform layer secondary to abnormal perifoveal retinal capillary permeability. The edema is termed "cystoid" as it appears cystic; however, lacking an epithelial coating, it is not truly cystic. The cause for CME can be remembered with the mnemonic "DEPRIVEN" (diabetes, epinepherine, pars planitis, retinitis pigmentosa, Irvine-Gass syndrome, venous occlusion, E2-prostaglandin analogues, nicotinic acid/niacin).

Diabetic macular edema (DME) is similarly caused by leaking macular capillaries. DME is the most common cause of visual loss in both proliferative, and non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy.[9]

Treatment

[edit]Macular edema sometimes occurs for a few days or weeks (sometimes even much longer) after cataract surgery, but most such cases can be successfully treated with NSAID or cortisone eye drops. Prophylactic use of Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs has been reported to reduce the risk of macular edema to some extent.[10] Higher frequency use of topical steroids provides benefit in difficult to treat cases.[11]

Diabetic macular edema may be treated with laser photocoagulation, reducing the chance of vision loss.[12]

In 2010, the US FDA approved the use of Lucentis intravitreal injections for macular edema.[13]

Iluvien, a sustained release intravitreal implant developed by Alimera Sciences, has been approved in Austria, Portugal and the U.K. for the treatment of vision impairment associated with chronic diabetic macular edema (DME) considered insufficiently responsive to available therapies. Additional EU country approvals are anticipated.[14]

In 2013 Lucentis by intravitreal injection was approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in the UK for the treatment of macular edema caused by diabetes[15] and/or retinal vein occlusion.[16]

On July 29, 2014, Eylea (aflibercept), an intravitreal injection produced by Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., was approved to treat DME in the United States.[17]

Research

[edit]In 2005, steroids were investigated for the treatment of macular edema due to retinal blood vessel blockage such as CRVO and BRVO.[18]

A 2014 Cochrane Systematic Review studied the effectiveness of two anti-VEGF treatments, ranibizumab and pegaptanib, on patients with macular edema caused by CRVO.[19] Participants on both treatment groups showed a reduction in macular edema symptoms over six months.[19]

Another Cochrane Review examined the effectiveness and safety of two intravitreal steroid treatments, triamcinolone acetonide and dexamethasone, for patients with from CRVO-ME.[20] The results from one trial showed that patients treated with triamcinolone acetonide were significantly more likely to show improvements in visual acuity than those in the control group, though outcome data was missing for a large proportion of the control group. The second trial showed that patients treated with dexamethasone implants did not show improvements in visual acuity, compared to patients in the control group.

Intravitreal injections and implantation of steroids inside the eye may result in a small improvement of vision for people with chronic or refractory diabetic macular edema.[21] There is low certainty evidence that there does not appear to be any additional benefit of combining anti-VEGF and intravitreal steroids when compared to either treatment alone.[22]

Anti‐tumour necrosis factor agents have been proposed as a treatment for macular oedema due to uveitis but a Cochrane Review published in 2018 found no relevant randomised controlled trials.[23]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ 'Oedema' is the standard form defined in the Concise Oxford English Dictionary (2011), with the precision that the spelling in the United States is 'edema'.

- ^ a b "What Causes Macular Edema". American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "What is Age-Related Macular Degeneration?". American Academy of Ophthalmology. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Laly DR (5 March 2014). "Pseudophakic Cystoid Macular Edema". Review of Ophthalmology. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "Complications of Uveitis". Her Majesty's Government, UK. 27 January 2015. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Lusby FW (8 May 2014). "Retinal Vein Occlusion". Medline Plus. US Library of Medicine. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Abaasi O (11 June 2009). "Common Medications That May Be Toxic To The Retina". Review of Ophthalmology. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "Medication Cautions in Macular Degeneration". American Macular Degeneration Foundation. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ Varma R, Bressler NM, Doan QV, Gleeson M, Danese M, Bower JK, et al. (November 2014). "Prevalence of and risk factors for diabetic macular edema in the United States". JAMA Ophthalmology. 132 (11): 1334–40. doi:10.1001/jamaophthalmol.2014.2854. PMC 4576994. PMID 25125075.

- ^ Lim BX, Lim CH, Lim DK, Evans JR, Bunce C, Wormald R (November 2016). "Prophylactic non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the prevention of macular oedema after cataract surgery". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2016 (11): CD006683. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006683.pub3. PMC 6464900. PMID 27801522.

- ^ Campochiaro PA, Han YS, Mir TA, Kherani S, Hafiz G, Krispel C, Liu TY, Wang J, Scott AW, Zimmer-Galler (June 2017). "Increased Frequency of Topical Steroids Provides Benefit in Patients With Recalcitrant Postsurgical Macular Edema". Am. J. Ophthalmol. 178: 163–175. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2017.03.033. PMID 28392176.

- ^ Jorge, Eliane C; Jorge, Edson N; Botelho, Mayra; Farat, Joyce G; Virgili, Gianni; El Dib, Regina (2018-10-15). Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group (ed.). "Monotherapy laser photocoagulation for diabetic macular oedema". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (10): CD010859. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010859.pub2. PMC 6516994. PMID 30320466.

- ^ "GEN | News Highlights: FDA Green-Lights Genentech's Lucentis for Macular Edema following Retinal Vein Occlusion". Genengnews.com. Retrieved 2012-12-15.

- ^ "Iluvien gains marketing authorization in Portugal for chronic DME". OSN SuperSite, June 7, 2012. Retrieved June 20, 2012

- ^ "Ranibizumab for treating diabetic macular oedema". NICE Guidance. NICE. February 2013.

- ^ "Ranibizumab for treating visual impairment caused by macular oedema secondary to retinal vein occlusion". NICE Guidance. NICE. May 2013. Retrieved 30 January 2016.

- ^ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2014-07-30.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Steroid Injections vs. Standard Treatment for Macular Edema Due to Retinal Blood Vessel Blockage - Full Text View". ClinicalTrials.gov. 3 March 2008. Retrieved 2012-12-15.

- ^ a b Braithwaite T, Nanji AA, Lindsley K, Greenberg PB (May 2014). "Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor for macular oedema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2014 (5): CD007325. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007325.pub3. PMC 4292843. PMID 24788977.

- ^ Gewaily D, Muthuswamy K, Greenberg PB (September 2015). "Intravitreal steroids versus observation for macular edema secondary to central retinal vein occlusion". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (9): CD007324. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007324.pub3. PMC 4733851. PMID 26352007.

- ^ Rittiphairoj, Thanitsara; Mir, Tahreem A.; Li, Tianjing; Virgili, Gianni (November 17, 2020). "Intravitreal steroids for macular edema in diabetes". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2020 (11): CD005656. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005656.pub3. ISSN 1469-493X. PMC 8095060. PMID 33206392.

- ^ Mehta, Hemal; Hennings, Charles; Gillies, Mark C; Nguyen, Vuong; Campain, Anna; Fraser-Bell, Samantha (2018-04-18). "Anti-vascular endothelial growth factor combined with intravitreal steroids for diabetic macular oedema". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (4): CD011599. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd011599.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 6494419. PMID 29669176.

- ^ Barry RJ, Tallouzi MO, Bucknall N, Mathers JM, Murray PI, Calvert MJ, et al. (Cochrane Eyes and Vision Group) (December 2018). "Anti-tumour necrosis factor biological therapies for the treatment of uveitic macular oedema (UMO) for non-infectious uveitis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018 (12): CD012577. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012577.pub2. PMC 6516996. PMID 30562409.