Talk:Cell (biology)/NCBI leftover

merge/integrate with cell division, mitosis etc.[edit]

For most unicellular organisms, reproduction is a simple matter of cell duplication, also known as replication. But for multicellular organisms, cell replication and reproduction are two separate processes. Multicellular organisms replace damaged or worn out cells through a replication process called mitosis, the division of a eukaryotic cell nucleus to produce two identical daughter nuclei. To reproduce, eukaryotes must first create special cells called gametes—eggs and sperm—that then fuse to form the beginning of a new organism. Gametes are but one of the many unique cell types that multicellular organisms need to function as a complete organism.

Most unicellular organisms create their next generation by replicating all of their parts and then splitting into two cells, a type of asexual reproduction called binary fission. This process spawns not just two new cells, but also two new organisms. Multicellullar organisms replicate new cells in much the same way. For example, we produce new skin cells and liver cells by replicating the DNA found in that cell through mitosis. Yet, producing a whole new organism requires sexual reproduction, at least for most multicellular organisms. In the first step, specialized cells called gametes—eggs and sperm—are created through a process called meiosis. Meiosis serves to reduce the chromosome number for that particular organism by half. In the second step, the sperm and egg join to make a single cell, which restores the chromosome number. This joined cell then divides and differentiates into different cell types that eventually form an entire functioning organism.

Mitosis is the process by which the diploid nucleus (having two sets of homologous chromosomes) of a somatic cell divides to produce two daughter nuclei, both of which are still diploid. The left-hand side of the drawing demonstrates how the parent cell duplicates its chromosomes (one red and one blue), providing the daughter cells with a complete copy of genetic information. Next, the chromosomes align at the equatorial plate, and the centromeres divide. The sister chromatids then separate, becoming two diploid daughter cells, each with one red and one blue chromosome.

Mitosis[edit]

Every time a cell divides, it must ensure that its DNA is shared between the two daughter cells. Mitosis is the process of "divvying up" the genome between the daughter cells. To easier describe this process, let's imagine a cell with only one chromosome. Before a cell enters mitosis, we say the cell is in interphase, the state of a eukaryotic cell when not undergoing division. Every time a cell divides, it must first replicate all of its DNA. Because chromosomes are simply DNA wrapped around protein, the cell replicates its chromosomes also. These two chromosomes, positioned side by side, are called sister chromatids and are identical copies of one another. Before this cell can divide, it must separate these sister chromatids from one another. To do this, the chromosomes have to condense. This stage of mitosis is called prophase. Next, the nuclear envelope breaks down, and a large protein network, called the spindle, attaches to each sister chromatid. The chromosomes are now aligned perpendicular to the spindle in a process called metaphase. Next, "molecular motors" pull the chromosomes away from the metaphase plate to the spindle poles of the cell. This is called anaphase. Once this process is completed, the cells divide, the nuclear envelope reforms, and the chromosomes relax and decondense during telophase. The cell can now replicate its DNA again during interphase and go through mitosis once more.

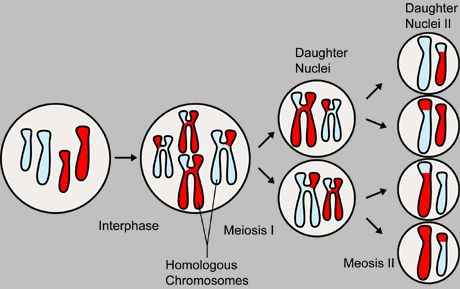

Meiosis, a type of nuclear division, occurs only in reproductive cells and results in a diploid cell (having two sets of chromosomes) giving rise to four haploid cells (having a single set of chromosomes). Each haploid cell can subsequently fuse with a gamete of the opposite sex during sexual reproduction. In this illustration, two pairs of homologous chromosomes enter Meiosis I, which results initially in two daughter nuclei, each with two copies of each chromosome. These two cells then enter Meiosis II, producing four daughter nuclei, each with a single copy of each chromosome.

Meiosis[edit]

Meiosis is a specialized type of cell division that occurs during the formation of gametes. Although meiosis may seem much more complicated than mitosis, it is really just two cell divisions in sequence. Each of these sequences maintains strong similarities to mitosis.

Meiosis I refers to the first of the two divisions and is often called the reduction division. This is because it is here that the chromosome complement is reduced from diploid (two copies) to haploid (one copy). Interphase in meiosis is identical to interphase in mitosis. At this stage, there is no way to determine what type of division the cell will undergo when it divides. Meiotic division will only occur in cells associated with male or female sex organs. Prophase I is virtually identical to prophase in mitosis, involving the appearance of the chromosomes, the development of the spindle apparatus, and the breakdown of the nuclear membrane. Metaphase I is where the critical difference occurs between meiosis and mitosis. In mitosis, all of the chromosomes line up on the metaphase plate in no particular order. In Metaphase I, the chromosome pairs are aligned on either side of the metaphase plate. It is during this alignment that the chromatid arms may overlap and temporarily fuse, resulting in what is called crossovers. During Anaphase I, the spindle fibers contract, pulling the homologous pairs away from each other and toward each pole of the cell. In Telophase I, a cleavage furrow typically forms, followed by cytokinesis, the changes that occur in the cytoplasm of a cell during nuclear division; but the nuclear membrane is usually not reformed, and the chromosomes do not disappear. At the end of Telophase I, each daughter cell has a single set of chromosomes, half the total number in the original cell, that is, while the original cell was diploid; the daughter cells are now haploid.

Meiosis II is quite simply a mitotic division of each of the haploid cells produced in Meiosis I. There is no Interphase between Meiosis I and Meiosis II, and the latter begins with Prophase II. At this stage, a new set of spindle fibers forms and the chromosomes begin to move toward the equator of the cell. During Metaphase II, all of the chromosomes in the two cells align with the metaphase plate. In Anaphase II, the centromeres split, and the spindle fibers shorten, drawing the chromosomes toward each pole of the cell. In Telophase II, a cleavage furrow develops, followed by cytokinesis and the formation of the nuclear membrane. The chromosomes begin to fade and are replaced by the granular chromatin, a characteristic of interphase. When Meiosis II is complete, there will be a total of four daughter cells, each with half the total number of chromosomes as the original cell. In the case of male structures, all four cells will eventually develop into sperm cells. In the case of the female life cycles in higher organisms, three of the cells will typically abort, leaving a single cell to develop into an egg cell, which is much larger than a sperm cell.

merge/integrate with transcription (genetics)[edit]

Of course, there are different proteins that direct transcription. The most important enzyme is RNA polymerase, an enzyme that influences the synthesis of RNA from a DNA template. For transcription to be initiated, RNA polymerase must be able to recognize the beginning sequence of a gene so that it knows where to start synthesizing an mRNA. It is directed to this initiation site by the ability of one of its subunits to recognize a specific DNA sequence found at the beginning of a gene, called the promoter sequence. The promoter sequence is a unidirectional sequence found on one strand of the DNA that instructs the RNA polymerase in both where to start synthesis and in which direction synthesis should continue. The RNA polymerase then unwinds the double helix at that point and begins synthesis of a RNA strand complementary to one of the strands of DNA. This strand is called the antisense or template strand, whereas the other strand is referred to as the sense or coding strand. Synthesis can then proceed in a unidirectional manner.

Although much is known about transcript processing, the signals and events that instruct RNA polymerase to stop transcribing and drop off the DNA template remain unclear. Experiments over the years have indicated that processed eukaryotic messages contain a poly(A) addition signal (AAUAAA) at their 3' end, followed by a string of adenines. This poly(A) addition, also called the poly(A) site, contributes not only to the addition of the poly(A) tail but also to transcription termination and the release of RNA polymerase from the DNA template. Yet, transcription does not stop here. Rather, it continues for another 200 to 2000 bases beyond this site before it is aborted. It is either before or during this termination process that the nascent transcript is cleaved, or cut, at the poly(A) site, leading to the creation of two RNA molecules. The upstream portion of the newly formed, or nascent, RNA then undergoes further modifications, called post-transcriptional modification, and becomes mRNA. The downstream RNA becomes unstable and is rapidly degraded.

Although the importance of the poly(A) addition signal has been established, the contribution of sequences further downstream remains uncertain. A recent study suggests that a defined region, called the termination region, is required for proper transcription termination. This study also illustrated that transcription termination takes place in two distinct steps. In the first step, the nascent RNA is cleaved at specific subsections of the termination region, possibly leading to its release from RNA polymerase. In a subsequent step, RNA polymerase disengages from the DNA. Hence, RNA polymerase continues to transcribe the DNA, at least for a short distance.

merge/integrate with translation (genetics)[edit]

The cellular machinery responsible for synthesizing proteins is the ribosome. The ribosome consists of structural RNA and about 80 different proteins. In its inactive state, it exists as two subunits: a large subunit and a small subunit. When the small subunit encounters an mRNA, the process of translating an mRNA to a protein begins. In the large subunit, there are two sites for amino acids to bind and thus be close enough to each other to form a bond. The "A site" accepts a new transfer RNA, or tRNA—the adaptor molecule that acts as a translator between mRNA and protein—bearing an amino acid. The "P site" binds the tRNA that becomes attached to the growing chain.

As we just discussed, the adaptor molecule that acts as a translator between mRNA and protein is a specific RNA molecule, the tRNA. Each tRNA has a specific acceptor site that binds a particular triplet of nucleotides, called a codon, and an anti-codon site that binds a sequence of three unpaired nucleotides, the anti-codon, which can then bind to the codon. Each tRNA also has a specific charger protein, called an aminoacyl tRNA synthetase. This protein can only bind to that particular tRNA and attach the correct amino acid to the acceptor site.

The start signal for translation is the codon ATG, which codes for methionine. Not every protein necessarily starts with methionine, however. Oftentimes this first amino acid will be removed in later processing of the protein. A tRNA charged with methionine binds to the translation start signal. The large subunit binds to the mRNA and the small subunit, and so begins elongation, the formation of the polypeptide chain. After the first charged tRNA appears in the A site, the ribosome shifts so that the tRNA is now in the P site. New charged tRNAs, corresponding the codons of the mRNA, enter the A site, and a bond is formed between the two amino acids. The first tRNA is now released, and the ribosome shifts again so that a tRNA carrying two amino acids is now in the P site. A new charged tRNA then binds to the A site. This process of elongation continues until the ribosome reaches what is called a stop codon, a triplet of nucleotides that signals the termination of translation. When the ribosome reaches a stop codon, no aminoacyl tRNA binds to the empty A site. This is the ribosome signal to break apart into its large and small subunits, releasing the new protein and the mRNA. Yet, this isn't always the end of the story. A protein will often undergo further modification, called post-translational modification. For example, it might be cleaved by a protein-cutting enzyme, called a protease, at a specific place or have a few of its amino acids altered.