The Icicle Thief

| The Icicle Thief | |

|---|---|

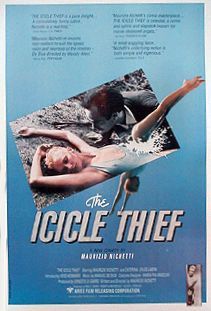

Film poster | |

| Directed by | Maurizio Nichetti |

| Written by | Mauro Monti Maurizio Nichetti |

| Story by | Maurizio Nichetti |

| Produced by | Ernesto Di Sabro |

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Mario Battistoni |

| Edited by | Rita Rossi |

| Music by | Manuel De Sica |

| Distributed by | Bambú, Reteitalia |

Release date |

|

Running time | 90 minutes |

| Country | Italy |

| Languages | Italian English |

| Box office | $1,231,622 (domestic)[1] |

The Icicle Thief (Italian: Ladri di saponette, lit. 'Soap Thieves') is a 1989 Italian comedy film directed by Maurizio Nichetti, titled in imitation of Vittorio De Sica's 1948 classic Italian neorealist film The Bicycle Thief (Italian: Ladri di biciclette). Some feel The Icicle Thief was created as a spoof of neorealism, which predominated Italian cinema after World War II. However, it is generally understood that the film is critical of the impact of consumerism on art, as suggested by the contrast between the nested film and commercials, and the apathy of Italian television viewers in recognising the difference between the two.[2] The film won the Golden St. George at the 16th Moscow International Film Festival.[3]

Plot[edit]

The movie begins with a film director, played by director Maurizo Nichetti himself, discussing his latest film on an intellectual Italian TV channel which is about to broadcast it at short notice in place of a more highly regarded competitor’s. His "masterpiece" follows the bleak travails of a poverty-stricken unemployed man (again played by Nichetti) who finds work in a chandelier factory, but cannot resist stealing one of the gleaming lights for his wife. The pompous director is initially pleased with the seriousness with which his work is analysed, but he then becomes distraught when his black-and-white opus is repeatedly interrupted by full-colour commercials. The TV audience, watching in their homes, are completely oblivious of the interruptions and the "outrages" perpetrated on the director’s artistic intentions.[4][5]

Nested film plot[edit]

The nested film borrows key elements from the Bicycle Thieves, with the protagonist family having the same first names from the original, and the director intending to end the film tragically. The director’s original plot followed the travails of Antonio Piermattei (Maurizo Nichetti) and his impoverished family: Antonio finds work in a chandelier factory, where he tries to steal one of the lights for his wife, Maria (Caterina Sylos Labini).

When Antonio manages to smuggle a chandelier out of the factory, he is supposed to be paralysed by a traffic accident with a truck while riding home with the chandelier (just after the plot diverges due to a power failure). The accident would have forced Maria into prostitution, with their two sons, Bruno (Federico Rizzo) and Paolo (Matteo Auguardi), ending up in an orphanage in the final scene.[6]

Plot divergence[edit]

A power failure in the studio causes a model (Heidi Komarek) from one of the commercials to end up in the nested film's universe and disrupt the plot. Maria, thinking that Antonio is having an affair with the model, enters the commercial universe by faking her death, causing the police in the film to accuse Antonio of murdering her.[6]

Nichetti is forced to enter the film universe to restore the original plot, but Bruno convinces Don Italo (Renato Scarpa) to shift the blame from Antonio to Nichetti for Maria's murder, after learning of Nichetti’s orphanage plot: this causes Nichetti to chase Bruno through the commercial universe before ending up in the commercial for floor wax, where Maria had been realising her aspiration as a singer.[7]

Actual ending[edit]

Back in the film universe, Antonio laments the apparent loss of Maria and Bruno, and the possibility of the model leaving him due to the grim nature of the film. However, Nichetti manages to convince Maria and Bruno to return to the film universe with shopping carts of modern-day goods, with the Piermattei family reunited the satisfaction of the viewer (Carlina Torta). Nichetti then attempts to return to the real world, only to be trapped in the film universe after the viewer switches off the television set before going to bed.[2]

Cast[edit]

- Maurizio Nichetti as himself, and Antonio Piermattei

- Caterina Sylos Labini as Maria Piermattei, Antonio’s wife

- Federico Rizzo as Bruno Piermattei, Antonio’s son

- Matteo Auguardi as Paolo Piermattei, Antonio’s baby son

- Renato Scarpa as Don Italo

- Heidi Komarek as the model

- Claudio G. Fava as the Film Critic

- Massimo Sacilotto and Carlina Torta as television viewers

Source: Maria Reviews[6]

Wordplay translation[edit]

The film's Italian title Ladri di saponette, a play on the Italian title of De Sica's film, means "Soap Thieves"; it is justified by dialogue where a boy is told not to use up all the soap when washing his hands, and his mother wonders if he is eating it. For English-speaking audiences, the title was changed to The Icicle Thief, playing on the English title of De Sica's film. This title was justified by changing the wording of the English subtitles when the characters talk about some chandeliers and one is stolen. In the original Italian dialogue they are said to sparkle like pearls (pèrle) and drops of water (gocce), but in the English subtitles, they look "like icicles" (which in Italian would be ghiaccioli).

Critical reception[edit]

Reviewing the film for the Los Angeles Times, Sheila Benson wrote, "Bless the Italians and their obsession with movies. Having created a permanent niche in the hearts of the world's movie sentimentalists with Cinema Paradiso, they now let loose their secret weapon, writer-director-actor and comic extraordinaire, Maurizio Nichetti". She found The Icicle Thief to be an "ingenious comedy", adding, "Pirandello rarely did it better and in The Purple Rose of Cairo Woody Allen didn't get this nuttily complex", before concluding that the film is "a lot like its creator--slight, ingenious and sneakily irresistible".[8]

In The Washington Post, Desson Howe was less impressed, beginning by noting, "The TV thing, right? It slices our sense of reality into 15-minute chunks. Its commercials ruin the dramatic integrity of the programs they interrupt. It turns us into dumb couch potatoes. It gives us limited attention spans. I said it gives us limited attention spans. These and other TV-loathing observations, as most of us have asserted in everything from organized junior-high class discussions to alcohol-induced dorm-room rantings, are inarguably true. But in The Icicle Thief, a satirical fantasy about the way television butchers the movies it puts on, Italian film director Maurizio Nichetti 'discovers' these insights as though for the first time". Howe goes on, "The parts of Icicle […] that bash the boob tube comprise the film's least enlightening elements; they're facile, almost sophomoric. […] But the parts which reveal, without self-conscious underlinings, the trashy TV culture in which we live, as well as the TV commercial switcheroos, are where it's worth watching". Overall, however, Howe concluded that: "things become a little too convoluted and Icicle joins that crowded group of Italian movies with an apparent inability to understand the concept of excess. But, as with many such films, the inner spirit frequently carries you over, and although Nichetti tells us practically nothing new about the global village, he certainly has fun with the possibilities".[9]

References[edit]

- ^ "The Icicle Thief (1990) - Box Office Mojo". www.boxofficemojo.com.

- ^ a b Caro, Mark (29 October 1989). "Wry Reality". Chicago Tribune. Chicago: Tribune Publishing. Archived from the original on 1 April 2020. Retrieved 1 April 2020.

- ^ "16th Moscow International Film Festival (1989)". MIFF. Archived from the original on 2013-03-16. Retrieved 2013-02-24.

- ^ James, Caryn (1990) "The Icicle Thief (1989)", New York Times, August 24, 1990. Retrieved 11 Sept. 2014

- ^ Michael Brooke (no date). “The Icicle Thief (1989) Plot Summary”, IMDb (no date). Retrieved 12 Sept. 2014

- ^ a b c Scheib, Richard (23 May 2003). "The Icicle Thief (1989)". Moria. Richard Scheib. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ Benson, Shelia (7 September 1990). "Movie Review: 'Icicle Thief' an Ingenious Parody". Los Angeles Times. El Segundo. Archived from the original on 31 March 2020. Retrieved 31 March 2020.

- ^ Benson, Sheila (7 September 1990). "MOVIE REVIEW: 'Icicle Thief' an Ingenious Parody". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles. Retrieved 15 October 2015.

- ^ Howe, Desson (7 September 1990). "'The Icicle Thief' (NR)". The Washington Post. Washington D.C. Retrieved 15 October 2015.