Idiospermum

| Idiospermum | |

|---|---|

| |

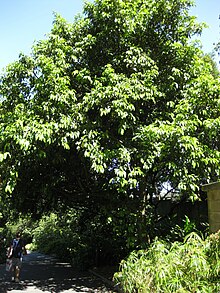

| Habit in cultivation | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Magnoliids |

| Order: | Laurales |

| Family: | Calycanthaceae |

| Genus: | Idiospermum S.T.Blake[4] |

| Species: | I. australiense

|

| Binomial name | |

| Idiospermum australiense | |

Idiospermum is a monotypic genus (that is, a genus that contains only one species) in the family Calycanthaceae. The sole included species is Idiospermum australiense − commonly known as idiotfruit, ribbonwood, or dinosaur tree − which is found only in two small areas of the tropical rainforests of northeastern Queensland, Australia. It is a relic of the ancient forests of Gondwana, surviving in very localised refugia for 120 million years, and displaying features (of the flowers in particular) that are almost identical to fossil records from that time. As such it provides an important insight into the very early evolution of flowering plants.

Description[edit]

Idiospermum australiense has, in contrast to its weighty evolutionary significance and its extraordinarily unique fruit, a rather nondescript overall appearance.[5][6] It is an evergreen tree growing to around 25 m (82 ft) tall,[7][8][9] with a maximum trunk diameter at breast height (DBH) of around 60 cm (24 in).[5][7] The leaves are simple (without lobes or divisions), opposite and glabrous (without hairs).[8][9] They measure up to 24 cm (9.4 in) long by 10 cm (3.9 in) wide, with 7−10 pairs of lateral veins.[8][9][10] They are held on petioles measuring 10 to 25 mm (0.4 to 1.0 in) long,[7][8][9] and the leaf blades exhibit numerous "oil dots" or pellucid glands (tiny, translucent spots) when held up against a strong light source.[9]

Flowers[edit]

The flowers may be solitary or in a panicle, produced either terminally or in the leaf axils.[9] They are sessile (without a stem) and measure about 2 cm (0.79 in) wide when fully open.[7] All floral organs − bracts, tepals, stamens, staminodes and carpels − are spirally arranged and there is no clear distinction between sepals and petals. The tepals are numerous with up to 52 per flower.[5] The stamens number 13 to 15, and arch forward over the opening of the floral cup; the stigma lies well below the stamens and staminodes.[7] The morphology of the gynoecium (the female parts of the flower that receive pollen and produce fruit) seen in the populations north of the Daintree River differ from that seen in populations south of Cairns (see Distribution and habitat). More than half of those in the north have been found to lack carpels (the structure that contains the ovary), and the remainder have one or (very rarely) two carpels.[11] One the other hand, all those from the south have at least one carpel, most have two, and some have up to five.[11]

Fruit[edit]

The fruit is, in botanical terms, a berry (a fruit derived from a single ovary of a single flower),[12] but in which all the layers surrounding the embryo − including the layers that, in other species, would form the fleshy outer layers and even the hard exterior coating of the seed − decay while still on the parent tree.[7]: 9 [13]: 38 What then falls from the tree is just the extremely large naked plant embryo, measuring roughly 5 cm (2.0 in) high and 6 cm (2.4 in) diameter).[8][10] This is the largest embryo of any flowering plant.[citation needed]

Another unique feature of the ribbonwood is the fact that the fruit contain multiple cotyledons (embryonic leaves within the seed). All other flowering plants have either one or two cotyledons.[14]

Phenology[edit]

Flowering of the ribbonwood occurs from early May through to mid June in the southern populations, and from June to mid September in the northern populations.[5]: 111 The species is dichogamous, that is the flowers are initially functionally female and then become functionally male. The flowers have a lifespan of between 10 and 16 days.[5]: 107 Initially, the stamens and staminodes (sterile appendages between the stamens and the carpel) which surround the stigma are held back, allowing access to the stigma and potential pollination. After 2−3 days the stamens start to close in, blocking access to the stigma. At the same time the anthers open, at which point the flower becomes functionally male. The tepals change colour during this process, being a creamy white when the flower first opens and darkening to red by the end of the process.[5]: 110 At any point in time during the flowering period, a tree may have flowers in a various stages of development.

Taxonomy[edit]

This species was originally described in 1912 as Calycanthus australiensis by the German botanist Ludwig Diels, based on material he collected himself in 1902.[7][15] He arrived in the area in June, a month that is now known as the peak of the flowering season for this species,[5][11] but he was apparently ill-prepared and was only able to collect flowers that had already fallen to the ground as well as a leafy branch.[5][7][15] His paper, titled Über primitive Ranales der australischen Flora, was published in the journal Botanische Jahrbücher für Systematik, Pflanzengeschichte und Pflanzengeographie, some ten years after he collected the specimens.[16] In the prologue to his description he lamented that it was incomplete, as he had not found a specimen of the fruit, nor flowers from the canopy. He also commented that the lack of a complete set of specimens is why he waited ten years before writing the description.[15]

It was not until 1972 that a complete description was published by the Australian botanist Stanley Thatcher Blake in the journal Contributions from the Queensland Herbarium. At the time Blake erected a new family − Idiospermaceae − for this taxon, but it is now widely accepted as belonging to the family Calycanthaceae[2][7][3]

The original holotype (i.e. the specimen of plant material collected and used to create the description) for this species was collected by Diels and taken to Berlin. In 1943 it was destroyed in a bombing raid, and a replacement (neotype) had to be chosen. This did not come about until the species was rediscovered, and the sample chosen was collected by the Australian botanist Stuart Worboys in 1998, from the same locality as the original.[10][6]

Etymology[edit]

The name Idiospermum derives from the Ancient Greek words idios meaning "individuality" or "peculiarity", and spérma meaning "seed", and is a reference to the unique characteristics of the fruits. The common name "idiot fruit" is a mistranslation of this.[9][17]

Distribution and habitat[edit]

The area occupied by the populations of Idiospermum australiense is a total of just 22.5 km2 (8.7 sq mi)[5]: 108 There are two main populations, the first (where Diels collected his samples), is approximately 50 km (31 mi) south of Cairns, in the vicinity of the Russell River and its tributaries. The other is approximately 120 km (75 mi) north of Cairns and around 10 km (6.2 mi) south of Cape Tribulation, in the areas of Cooper and Noah Creeks.[11] Both areas are rainforested lowlands at the foot of high, rain-attracting mountains, with annual rainfalls of more than 3,000 mm (120 in), and alluvial soils.[5][7] As the seeds of ribbonwood are only dispersed by gravity, the distribution of the species can only expand seawards.[14]

Ecology[edit]

Due to the enormous size of the seeds there are no animals that eat them and subsequently disperse them. Even the cassowary, well-known for its ability to swallow large fruit, does not eat these.[17] They are also known to be extremely toxic to cattle (see Discovery, loss and re-discovery) and probably to other animals as well.[14]

A large variety of insects, mostly beetles and thrips, are attracted by the scent and colour of the flower, and they in turn attract predators such as spiders and ants. Only the beetles and thrips appear to take a role in pollination, which is completed only when an insect first visits a flower in the male phase and then carries pollen to a flower in the female phase.[5][17]

Discovery, loss and re-discovery[edit]

The first European-Australians to encounter this tree were timber cutters working the lowland forests between Innisfail and Cairns in the late 1800s. Word of their discovery caught the attention of the German botanist Ludwig Diels, who ventured to the area in 1902 to collect specimens.[7][14][15] He found one tree in flower but was unable to collect fresh flowers as they are produced high in the canopy. Instead he collected fallen flowers, a leafy twig, but crucially no fruit. He took the samples back to Berlin with him, and in his disappointment about the incomplete collection, forgot about the material for years.[7][15] By the time Diels published his paper (in which he noted that the species was rare and that he had the only known collections)[15] the lowland forests where he found it were being cleared for sugar cane farming, and were gone by the 1920s.[7] For the next 60 years the species was thought to have been lost.[14]

In 1971 a grazier by the name of John Nicholas, who had a property in farmland in the Cow Bay area north of the Daintree River, discovered some of his cattle had died unexpectedly after suffering spasms. Believing someone had poisoned them he called in the police.[6][7] A government veterinarian, Doug Clague, examined the beasts and found large, unknown seeds in their stomachs, which appeared to have fallen from a particular tree on the property.[6][7] He sent the "seeds" and some flowers from the tree to the Queensland Herbarium for identification. There, the botanist Stanley Thatcher Blake, on seeing the flowers, suspected that they were from the long lost Calycanthus australiensis (as it was still known at the time).[6]

Blake was eager to undertake a detailed study of the plant and visited the property himself a short time after, where he collected material from both the farm and from remnant forest along a nearby creek.[7] More specimens were collected by others, including Len Webb and Geoff Tracey of the CSIRO Rainforest Ecology Research Unit, and also Bernard Hyland from the Commonwealth Forestry and Timber Bureau in Atherton, who all collected material in the area of Noah Creek, the only other watershed between Cow Bay and Cape Tribulation. Upon closer inspection of the fruit and the flower specimens together, along with details of the size of the tree, it soon became apparent to Blake that this was not a species of Calycanthus, and he raised a new genus, Idiospermum, to accommodate it.[6][7][18]

Conservation[edit]

Although this species has a very restricted range and has lost of much of its former habitat, the remaining areas in which it occurs are now protected. Accordingly it is listed by the Queensland Department of Environment and Science as least concern.[1] As of 9 April 2023[update], it has not been assessed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Gallery[edit]

-

Royal Botanic Gardens, Sydney, Dec 2010

-

Foliage, Cairns Botanic Gardens, April 2023

-

Twig and leaves, Cairns Botanic Gardens, April 2023

-

Multiple seedlings from a single "fruit"

-

Cairns Botanic Gardens, April 2023

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Species profile—Idiospermum australiense". Queensland Department of Environment and Science. Queensland Government. 2022. Retrieved 9 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Idiospermum australiense". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI). Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research, Australian Government. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ a b "Idiospermum australiense (Diels) S.T.Blake". Plants of the World Online. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Idiospermum". Australian Plant Name Index (APNI). Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research, Australian Government. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Worboys, S.J.; Jackes, B.R. (2005). "Pollination Processes in Idiospermum australiense (Calycanthaceae), an arborescent basal angiosperm of Australia's Tropical Rain Forests". Plant Systematics and Evolution. 251 (2): 107–117. doi:10.1007/s00606-004-0226-z. JSTOR 23655181. S2CID 25753048. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Heathcote, Angela (27 July 2017). "The Idiot Fruit Tree". Australian Geographic. Australian Geographic Society. Retrieved 2 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Blake, S.T. (1972). "Idiospermum (Idiospermaceae), a new genus and family for Calycanthus australiensis". Contributions from the Queensland Herbarium. 12 (5): 1–37. JSTOR 41781972. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Jessup, L.W. (2022). Kodela, P.G. (ed.). "Idiospermum australiense". Flora of Australia. Australian Biological Resources Study, Department of Climate Change, the Environment and Water: Canberra. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cooper, Wendy; Cooper, William T. (June 2004). Fruits of the Australian Tropical Rainforest. Clifton Hill, Victoria, Australia: Nokomis Editions. p. 232. ISBN 9780958174213.

- ^ a b c F.A. Zich; B.P.M Hyland; T. Whiffen; R.A. Kerrigan. "Idiospermum australiense". Australian Tropical Rainforest Plants (RFK8). Centre for Australian National Biodiversity Research (CANBR), Australian Government. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- ^ a b c d Worboys, Stuart J. (2003). "Polycarpelly in Idiospermum australiense (Calycantaceae)". Austrobaileya. 6 (3): 553–556. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ Romanov, Mikhail S.; Endress, Peter K.; Bobrov, Alexey V.F.Ch.; Yurmanov, Anton A.; Romanova, Ekaterina S. (2018). "Fruit structure of Calycanthaceae (Laurales): Histology and Development". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 179 (8): 616–634. doi:10.1086/699281. S2CID 92794556.

- ^ Staedler, Yannick M.; Weston, Peter H.; Endress, Peter K. (2009). "Comparative Gynoecium structure and development in Calycanthaceae (Laurales)" (PDF). International Journal of Plant Sciences. 170 (1): 21–41. doi:10.1086/593045. S2CID 84325229.

- ^ a b c d e "The green dinosaur". Wet Tropics Management Authority. Queensland Government. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Diels, Friedrich Ludwig Emil (1912). "Über primitive Ranales der australischen Flora". Botanische Jahrbücher für Systematik, Pflanzengeschichte und Pflanzengeographie. 48 (Beibl. 107): 7–13. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ "Calycanthus australiensis". International Plant Names Index (IPNI). Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. 2021. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ a b c Worboys, Stuart (15 September 2018). "It's hard to spread the idiot fruit". The Conversation. The Conversation Media Group. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- ^ Tracey, John Geoffrey (1994). John Tracey interviewed by Gregg Borschmann in the People's forest oral history project (interview). Interview by Gregg Borschmann.

External links[edit]

Data related to Idiospermum australiense at Wikispecies

Data related to Idiospermum australiense at Wikispecies Media related to Idiospermum australiense at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Idiospermum australiense at Wikimedia Commons- The story of the rediscovery of the Idiospermum by local resident Prue Hewett

- View a map of historical sightings of this species at the Australasian Virtual Herbarium

- View observations of this species on iNaturalist

- View images of this species on Flickriver