Portal:History of science

The History of Science Portal

The history of science covers the development of science from ancient times to the present. It encompasses all three major branches of science: natural, social, and formal. Protoscience, early sciences, and natural philosophies such as alchemy and astrology during the Bronze Age, Iron Age, classical antiquity, and the Middle Ages declined during the early modern period after the establishment of formal disciplines of science in the Age of Enlightenment.

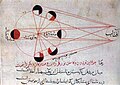

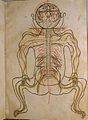

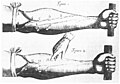

Science's earliest roots can be traced to Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia around 3000 to 1200 BCE. These civilizations' contributions to mathematics, astronomy, and medicine influenced later Greek natural philosophy of classical antiquity, wherein formal attempts were made to provide explanations of events in the physical world based on natural causes. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, knowledge of Greek conceptions of the world deteriorated in Latin-speaking Western Europe during the early centuries (400 to 1000 CE) of the Middle Ages, but continued to thrive in the Greek-speaking Byzantine Empire. Aided by translations of Greek texts, the Hellenistic worldview was preserved and absorbed into the Arabic-speaking Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age. The recovery and assimilation of Greek works and Islamic inquiries into Western Europe from the 10th to 13th century revived the learning of natural philosophy in the West. Traditions of early science were also developed in ancient India and separately in ancient China, the Chinese model having influenced Vietnam, Korea and Japan before Western exploration. Among the Pre-Columbian peoples of Mesoamerica, the Zapotec civilization established their first known traditions of astronomy and mathematics for producing calendars, followed by other civilizations such as the Maya.

Natural philosophy was transformed during the Scientific Revolution in 16th- to 17th-century Europe, as new ideas and discoveries departed from previous Greek conceptions and traditions. The New Science that emerged was more mechanistic in its worldview, more integrated with mathematics, and more reliable and open as its knowledge was based on a newly defined scientific method. More "revolutions" in subsequent centuries soon followed. The chemical revolution of the 18th century, for instance, introduced new quantitative methods and measurements for chemistry. In the 19th century, new perspectives regarding the conservation of energy, age of Earth, and evolution came into focus. And in the 20th century, new discoveries in genetics and physics laid the foundations for new sub disciplines such as molecular biology and particle physics. Moreover, industrial and military concerns as well as the increasing complexity of new research endeavors ushered in the era of "big science," particularly after World War II. (Full article...)

Selected article -

The presence of women in science spans the earliest times of the history of science wherein they have made significant contributions. Historians with an interest in gender and science have researched the scientific endeavors and accomplishments of women, the barriers they have faced, and the strategies implemented to have their work peer-reviewed and accepted in major scientific journals and other publications. The historical, critical, and sociological study of these issues has become an academic discipline in its own right.

The involvement of women in medicine occurred in several early western civilizations, and the study of natural philosophy in ancient Greece was open to women. Women contributed to the proto-science of alchemy in the first or second centuries CE During the Middle Ages, religious convents were an important place of education for women, and some of these communities provided opportunities for women to contribute to scholarly research. The 11th century saw the emergence of the first universities; women were, for the most part, excluded from university education. Outside academia, botany was the science that benefitted most from contributions of women in early modern times. The attitude toward educating women in medical fields appears to have been more liberal in Italy than in other places. The first known woman to earn a university chair in a scientific field of studies was eighteenth-century Italian scientist Laura Bassi. (Full article...)Selected image

The Flammarion woodcut is an enigmatic woodcut by an unknown artist. It is referred to as the "Flammarion woodcut" because its first documented appearance is in page 163 of Camille Flammarion's L'atmosphère: météorologie populaire ("The Atmosphere: Popular Meteorology," Paris, 1888).

The woodcut depicts a man, dressed as a medieval pilgrim and carrying a pilgrim's staff, peering through the sky as if it were a curtain to look at the inner workings of the universe. One of the elements of the cosmic machinery bears a strong resemblance to traditional pictorial representations of the "wheel in the middle of a wheel" described in the visions of the prophet Ezekiel (see Merkabah). The caption in Flammarion's book translates as "A missionary of the Middle Ages tells that he had found the point where the sky and the Earth touched..." The image accompanies a text which reads, in part, "What, then, is this blue sky, which certainly does exist, and which veils from us the stars during the day?" The woodcut is often described as being medieval due to its visual style, its fanciful vision of the world, and to what appears to be a depiction of a flat Earth.

Did you know

...that the travel narrative The Malay Archipelago, by biologist Alfred Russel Wallace, was used by the novelist Joseph Conrad as a source for his novel Lord Jim?

...that the seventeenth century philosophers René Descartes, Baruch Spinoza, and Gottfried Leibniz, along with their Empiricist contemporary Thomas Hobbes all formulated definitions of conatus, an innate inclination of a thing to continue to exist and enhance itself?

...that according to the controversial Hockney-Falco thesis, the rise of realism in Renaissance art, such as Jan Van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait (pictured), was largely due to the use of curved mirrors and other optical aids?

Selected Biography -

Joseph Priestley FRS (/ˈpriːstli/; 24 March 1733 – 6 February 1804) was an English chemist, natural philosopher, separatist theologian, grammarian, multi-subject educator, and liberal political theorist. He published over 150 works, and conducted experiments in several areas of science.

Priestley is credited with his independent discovery of oxygen by the thermal decomposition of mercuric oxide, having isolated it in 1774. During his lifetime, Priestley's considerable scientific reputation rested on his invention of carbonated water, his writings on electricity, and his discovery of several "airs" (gases), the most famous being what Priestley dubbed "dephlogisticated air" (oxygen). Priestley's determination to defend phlogiston theory and to reject what would become the chemical revolution eventually left him isolated within the scientific community. (Full article...)Selected anniversaries

April 25:

- 1710 - Birth of James Ferguson, Scottish astronomer (d. 1776)

- 1744 - Death of Anders Celsius, Swedish astronomer (b. 1701)

- 1770 - Death of Jean-Antoine Nollet, French abbot and physicist (b. 1700)

- 1840 - Death of Siméon-Denis Poisson, French mathematician (b. 1781)

- 1849 - Birth of Felix Klein, German mathematician (d. 1925)

- 1874 - Birth of Guglielmo Marconi, Italian inventor, recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics (d. 1937)

- 1900 - Birth of Wolfgang Ernst Pauli, Austrian-born physicist, Nobel Prize laureate (d. 1958)

- 1903 - Birth of Andrey Nikolayevich Kolmogorov, Russian mathematician (d. 1987)

- 1918 - Birth of Gerard Henri de Vaucouleurs, French astronomer (d. 1995)

- 1931 - Birth of Felix Berezin, Russian mathematician (d. 1980)

- 1953 - Francis Crick and James D. Watson publish Molecular structure of nucleic acids: a structure for deoxyribose nucleic acid describing the double helix structure of DNA.

- 1959 - The St. Lawrence Seaway, linking the North American Great Lakes and the Atlantic Ocean, officially opens to shipping.

- 1961 - Robert Noyce is granted a patent for an integrated circuit

- 2000 - Death of Lucien le Cam, French mathematician (b. 1924)

Related portals

Topics

General images

Subcategories

Things you can do

Help out by participating in the History of Science Wikiproject (which also coordinates the histories of medicine, technology and philosophy of science) or join the discussion.

Associated Wikimedia

The following Wikimedia Foundation sister projects provide more on this subject:

-

Commons

Free media repository -

Wikibooks

Free textbooks and manuals -

Wikidata

Free knowledge base -

Wikinews

Free-content news -

Wikiquote

Collection of quotations -

Wikisource

Free-content library -

Wikiversity

Free learning tools -

Wiktionary

Dictionary and thesaurus