Fluvoxamine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Luvox, others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a695004 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category |

|

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 53% (90% confidence interval: 44–62%)[3] |

| Protein binding | 77–80%[3][4] |

| Metabolism | Liver (primarily O-demethylation) Major: CYP1A2 Minor: CYP3A4 Minor: CYP2C19[3] |

| Elimination half-life | 12–13 hours (single dose), 22 hours (repeated dosing)[3] |

| Excretion | Kidney (98%; 94% as metabolites, 4% as unchanged drug)[3] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.125.476 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

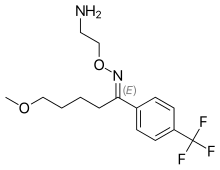

| Formula | C15H21F3N2O2 |

| Molar mass | 318.340 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| | |

Fluvoxamine, sold under the brand name Luvox among others, is an antidepressant of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class.[6] It is primarily used to treat major depressive disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD),[7] but is also used to treat anxiety disorders[8] such as panic disorder, social anxiety disorder, and post-traumatic stress disorder.[9][10][11]

Fluvoxamine's side-effect profile is very similar to other SSRIs: constipation, gastrointestinal problems, headache, anxiety, irritation, sexual problems, dry mouth, sleep problems and a risk of suicide at the start of treatment by lifting the psychomotor inhibition, but these effects appear to be significantly weaker than with other SSRIs (except gastrointestinal side-effects).[12]

Although the many drug-drug interactions of fluvoxamine can be problematic (and may temper enthusiasm for its prescribing, advocation and usage to some), its tolerance-profile itself is actually superior in some respects to other SSRIs (particularly with respect to cardiovascular complications), despite its age.[13] Compared to escitalopram and sertraline, indeed, fluvoxamine's gastrointestinal profile may be less intense,[14] often being limited to nausea.[15] Mosapride has demonstrated efficacy in treating fluvoxamine-induced nausea.[16] It is also advised practice to divide total daily doses of fluvoxamine greater than 100 milligrams, with the higher fraction being taken at bedtime (e.g., 50 mg at the beginning of the waking day and 200 mg at bedtime). In any case, high starting daily doses of fluvoxamine rather than the recommended gradual titration (starting at 50 milligrams and gradually titrating, up to 300 if necessary) may predispose to nauseous discomfort.[17]

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines.[18]

Medical uses[edit]

In many countries (e.g., Australia,[19][20] the United Kingdom,[21] and Russia[22]) it is commonly used for major depressive disorder. Fluvoxamine is also approved in the United States for obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD),[23][7] and social anxiety disorder.[24] In Japan, it is also approved to treat OCD, social anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder.[25][26] Fluvoxamine is indicated for children and adolescents with OCD.[27] The NICE guidelines in the United Kingdom have, as of 2005, authorized its use for obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults and adolescents of any age and children over the age of 7.[medical citation needed]

There is evidence that fluvoxamine is effective for generalised social anxiety in adults, although, as with other SSRIs, some of the results may be compromised by having been funded by pharmaceutical companies.[28][29] Of the SSRIs, however, fluvoxamine, paroxetine and sertraline do appear consistent as viable treatments for generalised social anxiety.[30][31] Phenelzine,[32][33] brofaromine, venlafaxine, gabapentin, pregabalin and clonazepam represent other viable options for the pharmacological treatment of generalised social anxiety.[medical citation needed]

Fluvoxamine is also effective for treating a range of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents, including generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder and separation anxiety disorder.[34][35][36]

The drug works long-term, and retains its therapeutic efficacy for at least one year.[37] It has also been found to possess some analgesic properties in line with other SSRIs and tricyclic antidepressants.[38][39][40]

The average therapeutic dose for fluvoxamine is 100 to 300 mg/day, with 300 mg being the upper daily limit normally recommended. Obsessive-compulsive disorder, however, often requires higher doses; doses of up to 450 mg/day may be prescribed in this case.[41][42][43] In any case with fluvoxamine, treatment is generally begun at 50 mg and increased in 50 mg increments every 4 to 7 days until a therapeutic optimum is reached.[44]

Adverse effects[edit]

Fluvoxamine's side-effect profile is very similar to other SSRIs, with gastrointestinal side effects more characteristic of those receiving treatment with fluvoxamine.[3][23][19][21][45][46]

Common[edit]

Common side effects occurring with 1–10% incidence:

- Abdominal pain

- Agitation

- Anxiety

- Asthenia (weakness)

- Constipation

- Diarrhea

- Dizziness

- Dyspepsia (indigestion)

- Headache

- Hyperhidrosis (excess sweating)

- Insomnia

- Loss of appetite

- Malaise

- Nausea

- Nervousness

- Palpitations

- Restlessness

- Sexual dysfunction (including delayed ejaculation, erectile dysfunction, decreased libido, etc.)

- Somnolence (drowsiness)

- Tachycardia (high heart rate)

- Tremor

- Vomiting

- Weight loss

- Xerostomia (dry mouth)

- Yawning

Uncommon[edit]

Uncommon side effects occurring with 0.1–1% incidence:

- Arthralgia

- Confusional state

- Cutaneous hypersensitivity reactions (e.g. oedema [buildup of fluid in the tissues], rash, pruritus)

- Extrapyramidal side effects (e.g. dystonia, parkinsonism, tremor, etc.)

- Hallucination

- Orthostatic hypotension

Rare[edit]

Rare side effecs occurring with 0.01–0.1% incidence:

- Abnormal hepatic (liver) function

- Galactorrhoea (expulsion of breast milk unrelated to pregnancy or breastfeeding)

- Mania

- Photosensitivity (being abnormally sensitive to light)

- Seizures

Unknown frequency[edit]

- Akathisia – a sense of inner restlessness that presents itself with the inability to stay still

- Bed-wetting

- Bone fractures

- Dysgeusia

- Ecchymoses

- Glaucoma

- Haemorrhage

- Hyperprolactinaemia (elevated plasma prolactin levels leading to galactorrhoea, amenorrhoea [cessation of menstrual cycles], etc.)

- Hyponatraemia

- Mydriasis

- Neuroleptic malignant syndrome – practically identical presentation to serotonin syndrome except with a more prolonged onset

- Paraesthesia

- Serotonin syndrome – a potentially fatal condition characterised by abrupt onset muscle rigidity, hyperthermia (elevated body temperature), rhabdomyolysis, mental status changes (e.g. coma, hallucinations, agitation), etc.

- Suicidal ideation and behaviour

- Syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

- Urinary incontinence

- Urinary retention

- Violence towards others[47]

- Weight changes

- Withdrawal symptoms

Interactions[edit]

Fluvoxamine inhibits the following cytochrome P450 enzymes:[48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][excessive citations]

- ^ Use During Pregnancy and Breastfeeding

- ^ Anvisa (31 March 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published 4 April 2023). Archived from the original on 3 August 2023. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Product Information Luvox". TGA eBusiness Services. Abbott Australasia Pty Ltd. 15 January 2013. Archived from the original on 9 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ van Harten J (March 1993). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 24 (3): 203–220. doi:10.2165/00003088-199324030-00003. PMID 8384945. S2CID 84636672.

- ^ "Luvox". ChemSpider. Royal Society of Chemistry. Archived from the original on 15 November 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ "Fluvoxamine Maleate Information". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). 15 July 2015. Archived from the original on 29 November 2019. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ a b McCain JA (July 2009). "Antidepressants and suicide in adolescents and adults: a public health experiment with unintended consequences?". P & T. 34 (7): 355–378. PMC 2799109. PMID 20140100.

- ^ "Fluvoxamine for the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. The Research Unit on Pediatric Psychopharmacology Anxiety Study Group". The New England Journal of Medicine. 344 (17): 1279–1285. April 2001. doi:10.1056/NEJM200104263441703. PMID 11323729.

- ^ Figgitt DP, McClellan KJ (October 2000). "Fluvoxamine. An updated review of its use in the management of adults with anxiety disorders". Drugs. 60 (4): 925–954. doi:10.2165/00003495-200060040-00006. PMID 11085201. S2CID 265712201.

- ^ Irons J (December 2005). "Fluvoxamine in the treatment of anxiety disorders". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 1 (4): 289–299. PMC 2424117. PMID 18568110.

- ^ Asnis GM, Hameedi FA, Goddard AW, Potkin SG, Black D, Jameel M, et al. (August 2001). "Fluvoxamine in the treatment of panic disorder: a multi-center, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in outpatients". Psychiatry Research. 103 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/S0165-1781(01)00265-7. PMID 11472786. S2CID 40412606.

- ^ Vezmar, S. et al., « Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy of Fluvoxamine and Amitriptyline in Depression », J Pharmacol Sci, vol. 110, no 1, 2009, p. 98 – 104 (ISSN 1347-8648)

- ^ Westenberg HG, Sandner C (April 2006). "Tolerability and safety of fluvoxamine and other antidepressants". International Journal of Clinical Practice. 60 (4): 482–491. doi:10.1111/j.1368-5031.2006.00865.x. PMC 1448696. PMID 16620364.

- ^ Oliva V, Lippi M, Paci R, Del Fabro L, Delvecchio G, Brambilla P, et al. (July 2021). "Gastrointestinal side effects associated with antidepressant treatments in patients with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry. 109. Elsevier BV: 110266. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2021.110266. PMID 33549697. S2CID 231809760.

- ^ Irons J (December 2005). "Fluvoxamine in the treatment of anxiety disorders". Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment. 1 (4): 289–299. PMC 2424117. PMID 18568110.

- ^ Ueda N, Yoshimura R, Shinkai K, Terao T, Nakamura J (November 2001). "Characteristics of fluvoxamine-induced nausea". Psychiatry Research. 104 (3). Elsevier BV: 259–264. doi:10.1016/s0165-1781(01)00320-1. PMID 11728615. S2CID 38761139.

- ^ Ware MR (1 March 1997). "Fluvoxamine: A Review of the Controlled Trials in Depression". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 (suppl 5). Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc.: 15–23. ISSN 0160-6689. PMID 9184623. Archived from the original on 6 December 2022. Retrieved 1 December 2023.

- ^ World Health Organization (2023). The selection and use of essential medicines 2023: web annex A: World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 23rd list (2023). Geneva: World Health Organization. hdl:10665/371090. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2023.02.

- ^ a b Rossi S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ^ "Luvox Tablets". NPS MedicineWise. Archived from the original on 22 October 2018. Retrieved 22 October 2018.

- ^ a b Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65th ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ^ "Summary of Full Prescribing Information: Fluvoxamine". Drug Registry of Russia (RLS) Drug Compendium (in Russian). Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ^ a b "Fluvoxamine Maleate tablet, coated prescribing information". DailyMed. U.S. National Library of Medicine. 14 December 2018. Archived from the original on 19 October 2020. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- ^ "Luvox CR approved for OCD and SAD". MPR. 29 February 2008. Archived from the original on 28 August 2021. Retrieved 2 March 2019.

- ^ "2005 News Releases". Astellas Pharma. Archived from the original on 16 September 2018. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "International Approvals: Ebixa, Depromel/Luvox, M-Vax". www.medscape.com. Archived from the original on 29 October 2020. Retrieved 16 September 2018.

- ^ "Fluvoxamine Product Insert" (PDF). Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc. U.S. Food and Drug Administration. March 2005. Archived (PDF) from the original on 4 November 2022. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

- ^ Williams T, Hattingh CJ, Kariuki CM, Tromp SA, van Balkom AJ, Ipser JC, et al. (October 2017). "Pharmacotherapy for social anxiety disorder (SAnD)". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD001206. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001206.pub3. PMC 6360927. PMID 29048739.

- ^ Liu X, Li X, Zhang C, Sun M, Sun Z, Xu Y, et al. (July 2018). "Efficacy and tolerability of fluvoxamine in adults with social anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis". Medicine (Baltimore). 97 (28): e11547. doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000011547. PMC 6076099. PMID 29995828.

- ^ Williams, T., McCaul, M., Schwarzer, G., Cipriani, A., Stein, D. J., & Ipser, J. (2020). Pharmacological treatments for social anxiety disorder in adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Acta neuropsychiatrica, 32(4), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1017/neu.2020.6

- ^ Davidson J. R. (2003). Pharmacotherapy of social phobia. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. Supplementum, (417), 65–71. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0447.108.s417.7.x

- ^ Tancer, M. E., & Uhde, T. W. (1997). Role of serotonin drugs in the treatment of social phobia. The Journal of clinical psychiatry, 58 Suppl 5, 50–54.

- ^ Aarre T. F. (2003). Phenelzine efficacy in refractory social anxiety disorder: a case series. Nordic journal of psychiatry, 57(4), 313–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/08039480310002110

- ^ "Antidepressants for children and teenagers: what works for anxiety and depression?". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. 3 November 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_53342. S2CID 253347210. Archived from the original on 5 November 2022. Retrieved 7 November 2022.

- ^ Boaden K, Tomlinson A, Cortese S, Cipriani A (2 September 2020). "Antidepressants in Children and Adolescents: Meta-Review of Efficacy, Tolerability and Suicidality in Acute Treatment". Frontiers in Psychiatry. 11: 717. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00717. PMC 7493620. PMID 32982805.

- ^ Correll CU, Cortese S, Croatto G, Monaco F, Krinitski D, Arrondo G, et al. (June 2021). "Efficacy and acceptability of pharmacological, psychosocial, and brain stimulation interventions in children and adolescents with mental disorders: an umbrella review". World Psychiatry. 20 (2): 244–275. doi:10.1002/wps.20881. PMC 8129843. PMID 34002501.

- ^ Wilde MI, Plosker GL, Benfield P (November 1993). "Fluvoxamine. An updated review of its pharmacology, and therapeutic use in depressive illness". Drugs. 46 (5): 895–924. doi:10.2165/00003495-199346050-00008. PMID 7507038. S2CID 195691900.

- ^ Kwasucki J, Stepień A, Maksymiuk G, Olbrych-Karpińska B (2002). "[Evaluation of analgesic action of fluvoxamine compared with efficacy of imipramine and tramadol for treatment of sciatica--open trial]". Wiadomosci Lekarskie. 55 (1–2): 42–50. PMID 12043315.

- ^ Schreiber S, Pick CG (August 2006). "From selective to highly selective SSRIs: a comparison of the antinociceptive properties of fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, citalopram and escitalopram". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 16 (6): 464–468. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.11.013. PMID 16413173. S2CID 39278756.

- ^ Coquoz D, Porchet HC, Dayer P (September 1993). "Central analgesic effects of desipramine, fluvoxamine, and moclobemide after single oral dosing: a study in healthy volunteers". Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 54 (3): 339–344. doi:10.1038/clpt.1993.156. PMID 8375130. S2CID 8229797.

- ^ Seibell PJ, Hamblin RJ, Hollander E. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: Overview and standard treatment strategies. Psychiatric Annals. 2015 Jun 1;45(6):297-302.

- ^ Rivas-Vazquez, R.A. and Blais, M.A., 1997. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and atypical antidepressants: A review and update for psychologists. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 28(6), p.526.

- ^ Middleton, R., Wheaton, M.G., Kayser, R. and Simpson, H.B., 2019. Treatment resistance in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Treatment resistance in psychiatry: risk factors, biology, and management, pp.165-177.

- ^ Figgitt, D.P. and McClellan, K.J., 2000. Fluvoxamine: an updated review of its use in the management of adults with anxiety disorders. Drugs, 60, pp.925-954.

- ^ Taylor D, Paton C, Shitij K (2012). The Maudsley prescribing guidelines in psychiatry. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-470-97948-8.

- ^ "Faverin 100 mg film-coated tablets – Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Abbott Healthcare Products Limited. 14 May 2013. Archived from the original on 21 October 2013. Retrieved 21 October 2013.

- ^ Szalavitz M (7 January 2011). "Top Ten Legal Drugs Linked to Violence". Time. Archived from the original on 21 September 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2014.

- ^ Ciraulo DA, Shader RI (2011). Ciraulo DA, Shader RI (eds.). Pharmacotherapy of Depression (2nd ed.). Springer. p. 49. doi:10.1007/978-1-60327-435-7. ISBN 978-1-60327-435-7.

- ^ Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B (2010). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ Baumann P (December 1996). "Pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic relationship of the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 31 (6): 444–469. doi:10.2165/00003088-199631060-00004. PMID 8968657. S2CID 31923953.

- ^ DeVane CL, Gill HS (1997). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of fluvoxamine: applications to dosage regimen design". The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 58 (Suppl 5): 7–14. PMID 9184622.

- ^ DeVane CL (1998). "Translational pharmacokinetics: current issues with newer antidepressants". Depression and Anxiety. 8 (Suppl 1): 64–70. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1998)8:1+<64::AID-DA10>3.0.CO;2-S. PMID 9809216. S2CID 22297498.

- ^ Bondy B, Spellmann I (March 2007). "Pharmacogenetics of antipsychotics: useful for the clinician?". Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 20 (2): 126–130. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328017f69f. PMID 17278909. S2CID 23859992.

- ^ Kroon LA (September 2007). "Drug interactions with smoking". American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy. 64 (18): 1917–1921. doi:10.2146/ajhp060414. PMID 17823102.

- ^ Waknine Y (13 April 2007). "Prescribers Warned of Tizanidine Drug Interactions". Medscape News. Medscape. Archived from the original on 21 February 2013. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ "Fluvoxamine (Oral Route) Precautions". Mayo Clinic. Archived from the original on 6 March 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2018.