Abakuá

Abakuá, also sometimes known as Ñañiguismo, is an Afro-Cuban initiatory fraternity and religious tradition. The society is open only to men and those initiated take oaths to not reveal the secret teachings and practices of the order. It draws influence from fraternal associations in the Cross River region of present-day southeastern Nigeria and southwestern Cameroon.

Abakuá formed in Regla in 1836 among Afro-Cubans. After the Cuban Revolution, Abakuá continued to face persecution but benefitted from the liberalising reforms of the 1990s as it became increasingly important in the Cuban tourist industry.

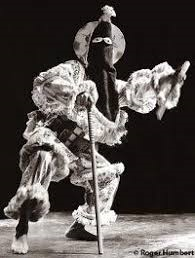

Rituals are called plantes and typically take place in a secluded room, the fambá. Many of the details of these ceremonies are kept secret although they usually involve drumming. Some of the Abakuá society's ceremonies take place in public. Most notable are the public parades on the Day of the Three Kings, when members dress as íremes, or spirits of the dead.

Definition[edit]

Abakuá represents a confraternity.[1] It is a religious group,[2] often seen as a religion by its practitioners,[3] and it seeks to provide spiritual protection for its members.[2] It also operates as a mutual aid society,[4] offering economic assistance to its members.[2] Only men are permitted entry,[5] and regard each other as brothers.[4] These members are referred to as Ñáñigos,[2] or sometimes as ecobios.[6] Members are bound to oaths of secrecy not to reveal details of the group's beliefs and practices.[7] Abakuá has been described as "an Afro-Cuban version of Freemasonry".[8]

Abakuá is one of three major Afro-Cuban religions present on the island, the other two being Santería, which derives largely from the Yoruba religion of West Africa, and Palo, which has its origins among the Kongo religion of Central Africa.[9] Another Afro-Cuban religion is Arará, which derives from practices among the Ewe and Fon.[10] In Cuba, practitioners of these traditions often see these different religions as offering complementary skills and mechanisms to solve problems.[11] Thus, some Abakuá members also practice Palo,[12] or Santería.[13]

Membership[edit]

Operating along a highly organised structure,[14] the Abakuá society displays a complex hierarchy.[2] Different members play different functions in the society.[4] Members pay fees to join the society and subsequent dues, money which finances the operation of the society.[15]

Chapters are referred to as juegos, potencias, tierras, and partidos.[16] The creation of a new chapter requires the permission of the society’s elders as well as a collective consensus in favor of its establishment.[3] Each juego has between 13 and 25 dignitaries, or plazas, who govern it.[4] Each dignitary has a different title that indicate which ritual tasks are their responsibility.[17]

The oaths of loyalty to the Abakuá society's sacred objects, members, and secret knowledge taken by initiates are a lifelong pact that creates a sacred kinship among the members. The duties of an Abakuá member to his ritual brothers at times surpass even the responsibilities of friendship. The phrase "Friendship is one thing, and the Abakuá another" is often heard.[18]

Beliefs and practices[edit]

Origin story[edit]

This origin myth explains the exclusion of women from the society.[19] The myth is also re-enacted through a number of the society's rituals.[14]

Practices[edit]

The society's rituals are called plantes.[20] These include initiations, funerals, the naming of dignitaries, and the annual homage to Ekué.[4] The details of these rites are kept secret from non-members.[21]

Rituals often take place in a special room, the "room of mysteries", known as the fambá, irongo, or fambayín.[21] This room is prepared for rituals by the drawing of images, called anaforuana or firmas, on the space and objects within it.[20]

These are full of theatricality and drama, and consist of drumming, dancing, and chanting in the secret Abakuá language. Knowledge of the chants is restricted to Abakuá members. Cuban scholars have long thought that the ceremonies express Abakuá cultural history.[22]

Music[edit]

Music is central to Abakuá rituals.[4] Drumming plays an important role in Abakuá rituals, as it does in other Afro-Cuban traditions.[15] Abakuá chapters will often have two separate sets of drums, one used in public events and the other in private ceremonies.[4] These drums will be consecrated prior to ritual use and then fed with the blood of sacrificed animals.[4]

Public drumming ceremonies rely on the use of four drums, each typically cut from a single log and left undecorated except for an anaforuana marked onto the skin.[4] The largest of these drums is called the bonkó enchemiyá; it is approximately 1 metre tall and placed at a slight tilt when being played.[4] The other three drums, which are typically around 9 to 10 inches in height, are called enkomó.[23] The three are tuned to produce different types of sound; that which reaches the highest pitch is the binkomé, the middle is the kuchí yeremá, and the lowest is the obiapá or salidor.[23] The three enkomó are each placed under one harm and hit with the other, using fingers rather than the whole hand.[23] As well as these four drums, the public rituals are typically accompanied with two rattles, the erikundí, and a bell made from two triangular pieces of iron, the ekón.[4]

Private rituals involve four drums, the enkríkamo, ekueñón, empegó, and eribó or seseribó.[23] These four drums are decorated with at least one feathered staff, attached at the end with the skin.[23] They may also have a "skirt" of shredded fibers.[23] The eribó, which has four of the feathered staffs rather than just one, is constructed differently, having the skin attached to a hoop of flexible material.[24] Sacrificial offerings are placed over this drum, which represents the dignitary Isué.[25] The enkríkamo is used to convene the spirits of the dead, while the ekueñón is employed by the dignitary tasked with dispending justice and performing sacrifices, which the drum is expected to witness.[23] The empegó is played by the dignitary of the same name and is used to open and close ceremonies.[23]

Also important in rites is a drum called the ekve, which is kept concealed behind a curtain in the fambá.[23] The ekve is a single-headed wooden friction drum with three openings at the base, giving the impression of three legs.[25] It is played by rubbing a stick over the skin, with the resulting sound symbolising the voice of Tanze the fish.[25]

Although hermetic and little known even within Cuba, an analysis of Cuban popular music recorded from the 1920s until the present reveals Abakuá influence in nearly every genre of Cuban popular music. Cuban musicians who are members of the Abakuá have continually documented key aspects of their society's history in commercial recordings, usually in their secret Abakuá language. The Abakuá have commercially recorded actual chants of the society, believing that outsiders cannot interpret them. Because Abakuá represented a rebellious, even anti-colonial, aspect of Cuban culture, these secret recordings have been very popular.[26]

Day of the Three Kings[edit]

Members take part in the public carnival held on January 6, the Day of the Three Kings.[27] For this they wear elaborate outfits consisting of checkerboard cloth, a design perhaps influenced by a leopard skin pattern.[19] They also wear a conical headpiece that is topped by tassels, which is based on those of the Ejagham.[19] Dressing as íremes signifies the return of the dead to Earth.[6]

Language[edit]

The Abakua language was proposed by Nunez Cedeno (1985) to be a Spanish-based pidgin, with the main African lexical influence originating from the Efik language.[28]

History[edit]

Influences[edit]

Abakuá was heavily influenced by the Ékpè or leopard society, which existed among the settlements of the Cross River basin in what is now Nigeria and Cameroon during the 18th and 19th centuries.[1] Ékpè had emerged among 18th-century Efik people as a means of transcending ethnic and family barriers and thus facilitating business relations for the trade in palm oil and slaves to European merchants.[1] It was an all-male society, and members were expected to keep its rites a secret – those who revealed secrets to outsiders could be punished with death.[1] Some Europeans were also initiated into the group.[1]

Formation and early history[edit]

The first Abakuá group was formed in Regla in 1836.[16] From there, the society spread to Havana, Matanzas, and Cárdenas.[16] Although established among Afro-Cubans, it came to let in mulattos and whites.[29] As Ivor Miller noted, the requirements for admission became not race, but "a demonstration of a moral character as well as discretion."[30] In the 1860s, the society began to adopt the public display of Roman Catholic symbols.[31]

The creolized Cuban term Abakuá is thought to refer to the Abakpa area in southeast Nigeria, where the society was active. The first such societies were established by Africans in the town of Regla, Havana, in 1836.[32]

The society faced persecution in the 19th and early 20th centuries.[33] In Cuban society, the term Ñáñigos gained negative connotations, equivalent of English terms like "sorcerer" and "delinquent".[33] Rivalries between different lodges sometimes escalated into violence, contributing to the society's negative reputation in Cuban society.[34] For many in the Cuban establishment, Abakuá was regarded as being "linked to a culture of poverty and marginalization".[17] At the same time, some politicians in the republic courted the society's support, even printing electoral material in Erik.[17]

-

Painting of Nañigo celebration in Cuba, 1878.

-

Painting including an Ireme dancer (right) at a Three Kings Day celebration in Havana.

-

Painting of a "diablito" Ireme dancer in Cuba.

-

Painting of an Ireme dancer in a ceremony in Cuba.

After the Cuban Revolution[edit]

The Cuban Revolution of 1959 resulted in the island becoming a Marxist–Leninist state governed by Fidel Castro's Communist Party of Cuba.[35] Committed to state atheism, Castro's government took a negative view of Afro-Cuban religions,[36] with state persecution of Abakuá continuing through the 1960s and into the 1970s.[37] Following the Soviet Union's collapse in the 1990s, Castro's government declared that Cuba was entering a "Special Period" in which new economic measures would be necessary. As part of this, it selectively supported Afro-Cuban traditions, partly out of a desire to boost tourism.[38] Abakuá's relationship with the tourist industry helped to improve the society's reputation in Cuba.[33]

Spread to Florida[edit]

Cities with many Afro-Cuban immigrants in Florida, such as Key West and Ybor City, have had a religion known by observers as "Nañigo". It was referred to as "Carabali Apapa Abacua" by practitioners. By the 1930s much of the religion seemed to have disappeared from visibility.[39]

For Abakuá lodges to be formed, a structured initiation rite must be performed. This was difficult for immigrant Abakuá members to arrange who are estranged from established lodges in Cuba. For this reason, there is a debate as to whether the practices described as "Nañigo" were official Abakuá practices or simply imitations done by members estranged from official lodges. The term "Nañigo" was often used to describe any Afro-Cuban traditions practiced in Florida, and it is not reliable to use to describe any set of traditions with accuracy.[40]

No Abakuá lodges had been formed in Miami until 1998. When an Abakuá group declared its presence in Miami, Cuban Abakuá members denounced it because their lodge was not officially consecrated with the required sacred materials, which are found only in Cuba.[40]

Reception and influence[edit]

Successive Cuban governments have seen the society's juegos as potential centres for resistance to the government and establishment.[41] Fernández Olmos and Paravisini-Gebert noted that the society had exerted a "profound and pervasive creative influence" on Cuban music, art, and language.[42]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 99.

- ^ a b c d e Vélez 2000, p. 17.

- ^ a b Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 101.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Vélez 2000, p. 18.

- ^ Vélez 2000, p. 4; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 99.

- ^ a b Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 107.

- ^ Vélez 2000, p. 18; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 99.

- ^ "Religion in Cuba: Chango unchained". The Economist. 18 April 2015. Retrieved 25 April 2015.

- ^ Mason 2002, p. 88; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 33.

- ^ Hagedorn 2001, pp. 22–23, 105.

- ^ Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 196.

- ^ Ochoa 2010, p. 106; Espírito Santo, Kerestetzi & Panagiotopoulos 2013, p. 196.

- ^ Vélez 2000, p. 11; Hagedorn 2001, p. 170; Wedel 2004, p. 54.

- ^ a b Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 105.

- ^ a b Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 106.

- ^ a b c Vélez 2000, p. 17; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 100.

- ^ a b c Vélez 2000, p. 22.

- ^ Miller, “A Secret Society Goes Public", African Studies Review 43.1 (2000): 164.

- ^ a b c Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 103.

- ^ a b Vélez 2000, p. 18; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 106.

- ^ a b Vélez 2000, p. 18; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 105.

- ^ Miller, Ivor. “Cuban Abakuá Chants: Examining New Linguistic and Historical Evidence for the African Diaspora.” African Studies Review 48.1 (2005): 27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Vélez 2000, p. 19.

- ^ Vélez 2000, pp. 19–20.

- ^ a b c Vélez 2000, p. 20.

- ^ Miller, Ivor. "A Secret Society Goes Public", African Studies Review 43.1 (2000): 161.

- ^ Vélez 2000, p. 17; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 103.

- ^ Rafael A. Núñez Cedeño. “The Abakuá Secret Society in Cuba: Language and Culture.” Hispania 71, no. 1 (1988): 148–54. https://doi.org/10.2307/343234.

- ^ Vélez 2000, p. 17; Miller 2016, p. 197.

- ^ Miller 2016, p. 197.

- ^ Miller 2016, p. 199.

- ^ Miller, Ivor. "A Secret Society Goes Public: The Relationship Between Abakua and Cuban Popular Culture". African Studies Review 43.1 (2000): 161.

- ^ a b c Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 108.

- ^ Vélez 2000, p. 22; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 108.

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 83.

- ^ Hagedorn 2001, p. 197; Ayorinde 2007, p. 156.

- ^ Vélez 2000, p. 23; Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 108.

- ^ Hagedorn 2001, pp. 7–8; Castañeda 2007, p. 148; Wirtz 2007, p. 72.

- ^ Anderson, Jeffery (1974). Hoodoo, Voodoo, and Conjure, A Handbook (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 October 2021. Retrieved 31 March 2019.

- ^ a b Miller, Ivor (2014). Abakua Communities in Florida: Members of the Cuban Brotherhood in Exile (PDF).

- ^ Vélez 2000, p. 23.

- ^ Fernández Olmos & Paravisini-Gebert 2011, p. 110.

Sources[edit]

- Ayorinde, Christine (2007). "Writing Out Africa? Racial Politics and the Cuban regla de ocha". In Theodore Louis Trost (ed.). The African Diaspora and the Study of Religion. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 151–66. doi:10.1057/9780230609938_9. ISBN 978-1403977861.

- Castañeda, Angela N. (2007). "The African Diaspora in Mexico: Santería, Tourism, and Representations of the State". In Theodore Louis Trost (ed.). The African Diaspora and the Study of Religion. New York: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 131–50. doi:10.1057/9780230609938_8. ISBN 978-1403977861.

- Espírito Santo, Diana; Kerestetzi, Katerina; Panagiotopoulos, Anastasios (2013). "Human Substances and Ontological Transformations in the African-Inspired Ritual Complex of Palo Monte in Cuba". Critical African Studies. 5 (3): 195–219. doi:10.1080/21681392.2013.837285. S2CID 143902124.

- Fernández Olmos, Margarite; Paravisini-Gebert, Lizabeth (2011). Creole Religions of the Caribbean: An Introduction from Vodou and Santería to Obeah and Espiritismo (second ed.). New York and London: New York University Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-6228-8.

- Hagedorn, Katherine J. (2001). Divine Utterances: The Performance of Afro-Cuban Santería. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-1560989479.

- Mason, Michael Atwood (2002). Living Santería: Rituals and Experiences in an Afro-Cuban Religion. Washington DC: Smithsonian Books. ISBN 978-1588-34052-8.

- Miller, Ivor L. (2016). "Abakuá Photographic Essay". Afro-Hispanic Review. 35 (2): 197–204. JSTOR 44797206.

- Ochoa, Todd Ramón (2010). Society of the Dead: Quita Manaquita and Palo Praise in Cuba. Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0520256842.

- Vélez, María Teresa (2000). Drumming For The Gods: The Life and Times of Felipe Garcia Villamil, Santero, Palero and Abakua. Studies in Latin American and Caribbean Music. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1566397315.

- Wedel, Johan (2004). Santería Healing: A Journey into the Afro-Cuban World of Divinities, Spirits, and Sorcery. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813026947.

- Wirtz, Kristina (2007). Ritual, Discourse, and Community in Cuban Santería: Speaking a Sacred World. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0813030647.

Further reading[edit]

- Aaron Myers (1999). "Abakuás". Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience. Basic Books. p. 2.

- Article on Cuban Abakuá music written by Dr Ivor Miller at lameca.org